Treating Preschoolers Who Stutter - Solutions Within A Publicly Funded Program

|

About the presenter: Marlene Green currently works as a Speech-Language Pathologist for the York Region Preschool Speech and Language Program, Ontario, Canada as well as in private practice. She attended the Workshop for Specialists in Stuttering Therapy in 1992, and has continued to pursue her passion in this field. She has always had an active interest in self-help for people who stutter, and was involved in organizing the 4th World Congress for People Who Stutter in 1998, when she still lived in South Africa. She sat on the board of directors of the International Stuttering Association from 1998-2001 and is currently on the advisory board. She is also a board member of the Speech Foundation of Ontario. |

Treating Preschoolers Who Stutter -- Solutions Within A Publicly Funded Program

by Marlene Green

from Canada

It was heartbreaking to watch our little girl work so hard to do what comes effortlessly to some: to speak. She struggled, learning how to move her mouth, lips and tongue to make each sound, and then to combine these sounds into words. Therapy was hard work and progress was slow. After 6 months of intensive therapy, Maddie's vocabulary was up to 15 word approximations. We were so very proud of her - learning and working so very hard, adding new sounds and words to her repertoire all the time. When Maddie turned four, she had a vocabulary of over 200 words and was becoming more confident in her speaking abilities.

Then suddenly, she started stuttering. At first we thought it was just a fluke - she was having a rough day. But as the days passed, her stuttering became worse. There was repetition, prolongation, blocking. She became frustrated and angry. She started to say "Never mind", not wanting to have to struggle to get her words out. Those words that she worked so very hard to say.

We were devastated. Our little girl was finally learning how to talk, and now she was stuttering. What kind of therapy would she need now? How would she be able to learn new words if she couldn't get the old words out? What about her already fragile self esteem?"

(Rhonda -the mother of Maddie)

Introduction:

In speech therapy settings funded entirely by a limited public budget, individual treatment is often a luxury, and creative solutions have to be developed for handling a large caseload while still providing best-practice intervention. Such is the case in Ontario, Canada, where the government funds a province-wide initiative to identify communication disorders and provide intervention for children up until their entry into senior kindergarten at around 5 years old. This includes the York Region Preschool Speech and Language Program (YRPSLP) amongst other such programs. When it comes to treating children who stutter, who without appropriate therapy run the risk of increased or chronic stuttering, it is YRPSLP's policy to provide intervention as quickly as possible.

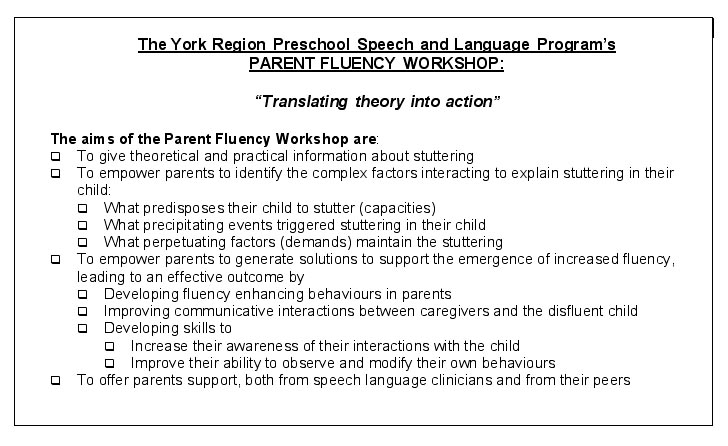

The focus of this paper is the protocol developed by the YRPSLP to handle all stuttering referrals with an emphasis on The Parent Fluency Workshop. Underpinning the protocol is the philosophy of the demands/ capacities model of stuttering, with a major focus on the role of parents as intervention partners.

Parents are frequently upset and overwhelmed with anxiety at the prospect of their child facing a lifetime of stuttering, and it is important that their needs, as well as those of the child, are dealt with sensitively and supportively to enable them to cope with the challenges facing them. The impact of parents' stories of their experiences as they try to help their children learn to communicate is invaluable in helping other parents as well as the clinicians treating them. To illustrate this presentation, I will draw on Rhonda's story as she continues to support her daughter, Maddie, in her quest to master communication.

The YRPSLP Protocol:

Two types of children are treated for fluency disorders in our program - those who are referred primarily because they stutter, and those who are currently enrolled in the program for other conditions and who have begun to stutter during their course of treatment.

In the case of new referrals parents complete a detailed questionnaire and an assessment is arranged as soon as possible (within 3 months). Because of the time constraints imposed by our budget, the assessment takes the form of a screening in order to decide whether treatment will be offered. If the child is stuttering or considered to be at risk for stuttering, the family is invited to attend the first step of our comprehensive treatment program: the six session Parent Fluency Workshop (PFWS). The screening assessment relies to a large degree on parental report because, although children often do not display signs of stuttering during the assessment, if the parents describe a high frequency of syllable repetitions, prolongations or blocks, the child is considered to stutter or be at risk for stuttering. In addition, information about demands is gathered from the questionnaire, parental report and an observation of a parent-child interaction. Finally the clinician briefly screens communication skills, to broadly identify "capacities" in terms of the development of language, articulation, social communication, attention and sensory difficulties, with a view to further assessment and appropriate intervention if necessary. If stuttering is observed or described by the parents, or if there are risk factors, the Parent Fluency Workshop is offered. At the assessment, parents are given information about stuttering, including a brief review of demands/capacities concepts, and some strategies to manage the stuttering which include slowing down their speech rate, reducing questions and responding to the message rather than the way in which the child speaks. It is also suggested that they reduce environmental demands. A list of helpful websites is also given to families.

Not infrequently, clinicians are faced with managing the treatment of a child who begins to stutter while attending therapy for any of a number of other communication disorders. We often face these decisions during the treatment of articulation disorders originating from either phonological or motor speech difficulties. It is proposed that the attempt to learn the new sounds and motor patterns is often too demanding of the child's capacities at that time. This situation has also been found when children in our program are working hard to acquire new language structures. Sometimes, a child with Down syndrome, hearing loss or autism also starts to stutter. In these situations, therapy (and the emphasis on having to practice their targets) is generally discontinued and the parents are counseled and enrolled in the next available PFWS.

The wait time for a PFWS is often 3-6 months. During this time parents are encouraged to implement suggestions and to contact the assessing clinician if they become more anxious or if stuttering worsens. If the stuttering resolves during this waiting period, because of the cyclic nature of stuttering, the child is still monitored for 3 months and then discharged if stuttering does not recur.

The Parent Fluency Workshop:

The first step in the therapy journey is the Parent Fluency Workshop, a 6-session group parent program. The Parent Fluency Workshop is conceptualized to be therapy rather than solely for the sharing information and is interactive. It is based on the premise that parents will execute effective strategies more consistently if they understand the reasons for doing so, especially if they have worked out the solutions themselves. Participation also offers the parents an opportunity to benefit from the emotional support of both their peers and the clinician. An added benefit is that there is usually at least one parent in the group who stutters themselves, and this generally is very helpful in many ways including assisting other parents to demystify stuttering. Facts are balanced with solutions and emotions are supported while skills are enhanced.

While data from these workshops has not been formally analyzed (another consequence of budget constraints), approximately 40 families access these workshops annually. Parent feedback has been extremely positive, and families generally are able to increase their knowledge about stuttering, change their attitudes to both stuttering and parenting and acquire strategies for improved interaction and the enhancement of fluency. Most parents have felt that the support of this group experience was invaluable. After the PFWS all families are followed and offered therapy within 4 months if the stuttering does not resolve. Our experience is that more than half of the families require no further intervention, despite the child having stuttered (with a range from at-risk to severe stuttering) for more than 6 months before the parents attend the PFWS.

The role of the clinician is to act as an information resource and as a facilitator for group support and decision making. Parents' value systems and strong sense of responsibility to their child are acknowledged and respected. Parents are involved in a process of active learning and problem solving, where behaviour and attitude change is seen to result from a process of self- discovery rather than solely through instruction. The six sessions involve the parents in four parent-only 2_-hour group sessions as well as two 1_ hour family sessions where they are videotaped interacting with their child while practicing the skills acquired. They are given an immediate opportunity to view and self-evaluate this tape as well as to receive feedback and suggestions from the clinician. The videotaping sessions occur after the 3rd group session and as the last session of the program.

The success of this PFWS is not only due to the information presented, but also because clinicians customize the information and support offered, based on each individual family's situation - there is no "one size fits all" solution.

What we do during the PFWS:

The PFWS is a constant "work in progress" so that current research and ideas are incorporated. The content of the PFWS reflects the ideas of many gifted clinicians and writers in the field of preschool stuttering who support the demands/capacities and interactionist approaches to the development of stuttering (in particular Starkweather et al, 1990; Rustin et al, 1996; Gregory et al, 1992; Hammer and Yaruss, 1999). The counseling strategies and expertise of many experts have also inspired the way in which the program is delivered (amongst others Botterill and Cook, 2003). Other influences have been the research of Oyler (2003) into sensitivity; Van Der Merwe (1990) into apraxia, as well as models developed by Caruso and Strand (1999), Levelt (1989) and De Nil (1999) to explain the complexity of neurophysiological events necessary to produce motor speech. Their ideas, together with those of my colleagues and myself, have coalesced to form the fabric of this program.

Approximately 8 to 12 sets of parents attend the PFWS, which is run approximately 5 times a year. Both parents are encouraged to attend as the PFWS is process-oriented and sharing only of the factual information between sessions is not considered ideal. The 4 group sessions are conducted within an interactive discussion format where probing questions are asked of the participants, according to a basic syllabus of information. After each discussion, in both large and small groups, the key points are summarized, and theory is translated into a practice exercise. Parents are given homework that encourages them to work on the concepts shared in that session. Throughout the program, the clinician models fluency enhancing strategies of slow, phrased speech with easy vocal onset, and demonstrates reflective listening. This is pointed out to the families early on in the program.

The materials we provide to families include those developed so generously and expertly by the Stuttering Foundation of America (If Your Child Stutters: A Guide for Parents; Stuttering and Your Child: Questions & Answers; The Child Who Stutters: To the Family Physician), Hammer and Yaruss (1999), amongst others.

Session 1:

The PFWS begins with a large group discussion where parents share their stories. At pivotal points throughout the discussion similarities and differences between the children are highlighted. This discussion has consistently been viewed by parents as a highlight of the program, helping them realise that they are not alone and allowing them to share their attitudes, concerns and expectations. Their stories include information about the way the stuttering began (sudden or gradual), how long the child has stuttered, a description of the child's stuttering and whether these have changed and the cyclical nature of stuttering. The clinician also facilitates a detailed exploration of the child's capacities and the internal and external demands facing the child. Rustin et al's (1996) framework forms an outline of this discussion which includes an examination of capacities:

Physiological factors such as genetics and family history, and the role of excitability, increased sensitivity, co-ordination, the presence of other conditions e.g. Down syndrome, autism, hearing loss, cerebral palsy etc. li>Linguistic factors such whether language development was early or delayed, whether there are phonological or motor speech concerns, whether the child has difficulty retrieving vocabulary or formulating grammatical sentences. Further questions are posed to help parents begin to understand the demands facing the child. li>Environmental and sociocultural factors include family configuration, time pressures, behavioural expectations, sibling competition, communication expectations, adult style of interaction and communication with the child (including speed, complexity, sophistication of vocabulary, multilingualism, questions, demand speech, interruptions, etc.)

The clinician then uses the information shared by the parents to present a detailed discussion defining stuttering as resulting from a complex interaction between the child's capacities and the demands facing them both externally and internally. A model of speech production and its complexity is presented to the parents (based on Levelt, 1989). Then parents are presented with an analogy of a balance scale or teeter-totter which will only be balanced if capacities and demands are equal. Acknowledging the predisposing factors underlying their child's stutter (capacities) is helpful in enabling the parents to modify the factors which keep the stuttering going, the demands. Parents are therefore encouraged to respect the child's innate capacities (which will by nature evolve as the child matures) by reducing demands.

Their homework involves them in reviewing their own child's capacities and the demands placed on him/her. Parents complete a speech observation diary which will help them accurately describe their child's stutter. They make note of when and with whom stuttering occurs and what factors are present (e.g. internal factors like fatigue, hunger or excitement; external factors e.g. time pressure, sibling competition, interruptions; or linguistic factors e.g. trying to use complex grammar or vocabulary, or describing an abstract concept). Parents are also asked to observe their child's natural speaking rate when playing alone, and they are invariably surprised to notice how slowly the child talks under these conditions. (This observation could be the topic of a future research project). Parents also complete the Sensory Profile (Dunn) to identify whether the child is having difficulty processing sensory experiences. We are fortunate to be able to access the consultative services of an occupational therapist through an allied program (York Region Early Intervention Services) to give parents strategies to manage sensory difficulties (another potential research project).

Sessions 2 and 3:

In these sessions parents discuss their findings from the Session 1 homework and problem solve helpful strategies to manage the demands they have identified. They are taught fluency enhancing strategies which they practice during the classes. Fundamental to these two sessions is the concept of child-centred interactions. In role-plays parents are taught to follow their child's lead in play and to get down to their level, establishing eye contact. They are taught to repeat and rephrase in order to close their child's communication circle and validate all their communication attempts, to delay these responses and not to interrupt. They learn to model slow speech, to comment rather than question. They are taught to model easy onsets and to break up longer sentences into phrases. However, they are cautioned that using these strategies only in response to a child's disfluent speech may reinforce the disfluent speech. Parents are also told that the use of these strategies and lifestyle/parenting changes are to be maintained for several months, and not to be stopped and started together with the child's stuttering/ fluent cycles. Rather, the consistent use of their strategies may prevent recurrence of stuttering.

They are taught how to manage transition times and times of excitement by using visual schedule boards. They learn about the power of telling stories to help their child prepare for a challenging time. They learn to manage sibling competition and turn-taking challenges. Parents are also helped to feel comfortable discussing the speech breakdowns with their child. An extremely important aspect of these classes is to teach parents to self-monitor their skills in order to be able to use them consistently.

Often the discussions lead parents to examine their parenting style and values around accelerating their children's development. They express anxiety about not equipping their children for the performance-based competitive settings of school and work. They talk about the school's expectations of what children should know before going into junior kindergarten, and frequently need to be educated about what skills typical children are expected to have acquired at any particular age.

At home they practice "special time" (Rustin et al, 1996) daily where they unconditionally follow their child's lead in play of the child's choice for five minutes. This is frequently a challenging change for many parents, who have often been conditioned to performance-based parenting, and who frequently have controlled, questioned and expanded on the child's ideas.

The first videotaping:

Both parents are encouraged to attend and they are each videotaped by the clinician for 5-10 minutes while following the child's lead in play. They then review the videotape and self-evaluate while using a form that we have developed for this purpose. We suggest that the child be removed from the room for these discussions, and if necessary, we bring the child back in for the clinician to model or to refine the parents' skills. Parents often give the feedback that, for the first time, they have started to enjoy playing with their children and that the children seek out this time together. Frequently parents also report an improvement in the child's level of fluency.

Session 4:

The fourth parent group session takes a different approach. Parents are taught to use their new communication style (slow, phrased, responsive etc.) to set their child up for fluency success. They learn to set up communication opportunities for their child in a hierarchy from very simple to more complex so that the child can practice fluent speech to the limits of his abilities. Parents are taught that they should set up these fluency practice-sessions at least once a day and that in these sessions they can choose the activity. One of the best such activities is reading with their child. The steps of the hierarchy go from the child singing or reciting together with the parent, to filling in single words at the end of predictable sentences, to filling in phrases, to generating sentences and then having conversations about the here and now, and then about more abstract concepts.

In addition parents are taught to introduce easy disfluencies into their own speech and are also taught the language of contrasting concepts.

The second videotaping:

In this session parents practice setting up a play situation using the hierarchic approach. They are taped, and feedback is given as before. Any other concerns they have at this time, as well as planning for further therapy, is discussed during this appointment.

What happens next?

The PFWS is the first step in the process of therapy, if the child continues to stutter. Because of our funding constraints, children in the York Region Preschool Speech and Language Program are only able to access two blocks of therapy (up to 8 sessions each) per year. These blocks are typically separated by 4 months. At the end of the PFWS all children are put on the waitlist for the next available therapy block. During this off-block period, parents are asked to contact their local YRPSLP office if they become concerned about their child's stutter worsening. They are then offered a consultation appointment. Otherwise the children are rechecked telephonically by parent report to see whether they still require treatment. If so, a block of therapy, often in a pair, is scheduled where parents and children are seen together, and the strategies learned at the PFWS are revised and put into practice. As stated before, many of the children stop stuttering during this period, and parents are encouraged to maintain their strategies. If this indirect method of therapy is not effective, other methods as well as other approaches are considered together with the parents before clinical decisions are made.

The children who both stutter and have other communication disorders are invited to attend the next available therapy block. It is our experience that frequently these children make large gains. Modeling the fluency enhancing strategies, seems to facilitate their motor speech and language development. If more specific work needs to be done, usually the clinician models for the child, but does not demand "work" from the child, as the extra effort involved so frequently precipitates a further cycle of stuttering.

The feedback:

Parents give feedback after the PFWS. The feedback is consistently positive, with many of the parents wishing that there were more sessions. Many parents have commented not only on improvements in their child's fluency, but also that their way of parenting and concepts about child-rearing have been changed. They also are unanimously positive about the support they gained form being in this type of group. Clearly some families benefit more than others, but almost all parents feel they have gained skills and confidence in implementing them. That so many of our children do not need follow up therapy, even though they had stuttered for more than 6 months before the PFWS, supports the effectiveness of this program.

Conclusion:

The clinicians of the York Region Preschool Speech and Language Program all agree that, even if we had no financial constraints, we would still offer the PFWS as the first part of the process of therapy. Extra funding would allow us to make the program longer as well as enabling us to offer more frequent one-on-one intensive therapy. In our program, dedicated clinicians have established a stuttering interest group that meets regularly. Our mentorship program allows for coaching and support of our staff. We also have in-service seminars and conference updates. It is our belief that our clinicians should constantly strive to develop their expertise and special sensitivity to equip them to deal effectively with families challenged by this most complex condition. In this way, our Parent Fluency Workshop will always remain a "work in progress".

We are thankful that we have the benefit of knowledgeable, caring practitioners that have given us the tools we need to help our little girl be the very best that she can be.

Tonight before she went to bed, she told us that when she grows up, she wants to be a teacher, a piano teacher and an artist. We know that she will be whatever she wants to be - she has the gift of confidence, which was given to her by all those who have helped us to help her to become the person she is today". (Rhonda)

Acknowledgements:

Many sources have been invaluable in developing the materials covered in the PFWS. I feel extremely fortunate to have been able to participate in self - help groups and conferences both in South Africa and internationally. These experiences have allowed me to interact with experts in the world of stuttering, not least of whom are the people who stutter and the parents of children who stutter. The clinical expertise and research of professionals in this field, as well as the long hours of discussion with many of them, have broadened my understanding of this most complex of conditions. I am deeply grateful to all the families who entrust the care of their children to our program - I learn from you with every encounter. I will remain indebted to all - my thoughts about stuttering have been influenced by all.

I particularly would like to acknowledge (amongst others), the Stuttering Foundation of America, all my friends at the International Stuttering Association, Speakeasy South Africa, the Canadian Association for People Who Stutter, and the International Fluency Association, including Hugo Gregory, Woody Starkweather, Lena Rustin, Willie Botterill, Francis Cook, Scott Yaruss, Nina Reardon, Libby Oyler, Anita van der Merwe, Nan Bernstein Ratner, Luc De Nil, Robert Kroll, Peggy Wahlhaus, Judy Kuster, Phil Schneider and David Shapiro and all my colleagues, past and present.

Bibliography:

Botterill, W. and Cook, F. (2003). The "How" and "Why" of parent groups. Seminar presented at 4th World Congress on Fluency Disorders, Montreal.

Caruso, A.J.; Max, L; and McLowry, M.T. (1999). Perspectives on stuttering as a motor speech disorder. In A.J. Caruso and E.A. Strand (eds.), Clinical Management of Motor Speech Disorders in Children (pp.319-344). New York: Thieme.

Caruso, A.J. and Strand E.A. (1999). Motor Speech Disorders in children: Definitions, background and a theoretical framework. In A.J. Caruso and E.A. Strand (eds.), Clinical Management of Motor Speech Disorders in Children (pp.1-27). New York: Thieme.

De Nil, L.F. (1999) Stuttering: A neurophysiological perspective. Chapter 7 in N.B. Ratner and E.C. Healey(Eds.) Stuttering research and practice: Bridging the gap(pp. 85-102). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum

Dunn, W. (1999) Sensory Profile. The Psychological Corporation.

Gregory, H., Gregory, C. Hill, D. and Campbell, J.(1992) Stuttering Therapy: A workshop for Specialists sponsored by Northwestern University and the Stuttering Foundation of America

Hammer, D. W. and Yaruss, J.S. (1999) Helping parents to facilitate young children's speech fluency. Paper presented at ASHA

Levelt, W.M. (1989). Speaking: From Intention to Articulation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Oyler, L. (2003). Dealing with heightened sensitivity in children who stutter. Paper presented at 4th World Congress on Fluency Disorders, Montreal.

Rustin, L., Botterill, W., and Kelman, E. (1996) Assessment and therapy for young dysfluent children: family interaction. London: Whurr Publishers, Ltd.

Starkweather, C.W., Gottwald, S. and Halfond, M. (1990). Stuttering Prevention: A Clinical Method. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall

Van Der Merwe, A. (1990). Personal communication