Therapeutic Listening

|

About the presenter: Joseph Donaher MA., CCC/SLP is the Program Coordinator of the Stuttering Program at the Center for Childhood Communication at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. He teaches graduate level courses on stuttering and fluency related disorders at Temple University where he is currently pursuing his Ph.D. under the guidance of Woody Starkweather. |

Therapeutic Listening

by Joseph Donaher and Michael Retzinger

from USA

Trust has been described as the main component in any healthy relationship. Unfortunately, many therapeutic relationships are not built on trust and therefore growth is often limited (Luterman, 2001). In order to strengthen the client/clinician relationship, one must realize that building trust takes work. Vital to this process is non-judgmental or active listening. Clinicians can use active listening strategies, such as seeking clarification, paraphrasing or reflecting, to demonstrate that they are interested, engaged and understanding (Shapiro, 1999). Manning (1999) pointed out that the best clinicians are described as "uncommonly effective in understanding, encouraging, supporting and guiding their clients." These skills foster the sense of trust between the client and the clinician and are paramount for successful intervention.

Speakers routinely use non-verbal cues to measure how they are engaging the listener. Eye contact, body posture and attention allow the listener to convey that they are attending. Parents can use these same strategies to demonstrate that they are listening and convey that the child is a good communicator. Nowhere is this more vital than when working with children who stutter. Given that many children who stutter experience speech related anxiety, listening skills are an effective treatment tool for decreasing communication apprehension, increasing self-esteem and increasing opportunities for interacting - even if the child stutters.

Listening can be defined in a variety of ways. Young children are told they are "good listeners" when they are obedient and comply to a directive. The same child would be accused of "not listening" if they failed to follow the command, regardless of whether or not it was heard. In the academic world, listening is often synonymous with the parroting back of data points or facts. In these settings, individuals are rewarded for retention of material and accessing this material in a specified way. If a student has difficulty with recalling the information or applying it in the specified manner, they are again accused of "not listening."

True listening in a relationship involves an active process where the listener attempts to empathize, understand and reflect upon the intended message. This type of listening does not come naturally and often sounds contrived or artificial. Listening can be taught and with a minimal amount of practice, professionals and parents can master the fundamentals. However, once the basic skills are taught, it is up to the individuals to commit to practicing and using them in everyday settings. It is unfortunate that many programs which train speech-language pathology students do not incorporate listening skills into their curriculums. It is common for psychology and counseling programs to spend a great deal of time on ways to effectively listen to and attend to your clients.

Woody Starkweather often commented that Speech-Language Pathologists have the knowledge of stuttering but psychologists and counselors have the tools to efficiently work on the disorder. David Luterman (2001) asked what is the value of technical expertise if one can not effectively communicate with a client? Considering that listening is at least half of the communicative process, it makes sense to make listening a significant part of any treatment approach when working with children who stutter (CWS). This would accomplish several things including:

- Demonstrating that stuttering is acceptable

- Developing a relationship based on trust

- Providing/modeling positive communicative interactions

- Supporting the individual as a communicator.

Besides incorporating listening into their own therapy routines, clinicians should transfer the knowledge, techniques, and strategies regarding listening to families of CWS.

To foster the development of self-esteem and confidence, families should address their children's effectiveness as communicators regardless of whether they are stuttering. What better way to show someone that they are presenting themselves in a positive light, than to actively listen to them and show them that you are interested in what they have to say. When parents are introduced to listening skills in therapy, they often report increased communicative interactions with their children. As a result, they switch the focus from stuttering to communication while demonstrating that they are not afraid of stuttering.

In an attempt to increase parent's use of active listening, Faber and Mazlish (1999) point out that when parents respond with advice, philosophy, or psychology, children may feel worse off and avoid sharing their emotions or discussing their issues. However, the authors suggest that if a listener responds with full attention, active listening, acknowledgement of emotional tone being expressed and permission for the speaker to continue, the speaker may feel less anxious, confused and/or upset. This in turn may lead to the speaker feeling better able to cope while encouraging them to continue communicating.

Several basic techniques are vital to active listening. These include: empathetic responses, honesty, commitment, body posturing and concentration. By responding with empathy, a listener is demonstrating that they acknowledge and accept the speaker's emotions and feelings (Faber & Mazlish, 1980). One way to achieve this is to describe what the speaker might be feeling. "You must have been scared" or "you must have been nervous." Listeners should avoid simple parroting back of what the speaker said as this usually sounds unnatural. Listeners must respond honestly to the speaker. If they do not understand something, be honest and ask a question for clarification. If they do not have time to listen at that specific moment, tell the speaker you are busy but arrange a time for listening in the immediate future.

Listening takes commitment both in learning the skills and in applying them naturally. Once a listener commits, they should relax, and release any extraneous thoughts that may interrupt the process. They should devote the time and concentrate on the speaker's intended message. In fact, when a professional or a parent is concentrating on listening, it becomes problematic to additionally focus on how the message is being delivered. They must remember that the goal is to convey to the speaker that you are keyed into what they are saying. The listener should not give advice, talk excessively, suggest topics, or ask unnecessary questions unless they are for clarification during this time.

Body proximity and the environment are important considerations for listening. Listeners should choose an environment that will be conducive to the interaction and actively move away from distractions. Loud or busy environments typically do not foster interactions and can make concentration and listening difficult. A location with minimal distractions is optimal to work on these strategies. The listener should be cognizant of their body posturing and proximity. Chairs cans be arranged, facing each other, about an arms length apart. Avoid sitting on opposite sides of a table as this can create distance between the individuals. The listener should adopt an open body posture, maintain good eye contact, and lean slightly forward towards the speaker. In this way, you are demonstrating that you are interested in listening and you are inviting the speaker to keep sharing. While it is productive to review strategies for active listening, it is often beneficial to discuss what to avoid when actively listening. Neukrug (1999) reported on common hindrances to listening. These include:

- Having preconceived notions regarding the speaker or the message that taint one's ability to truly hear what is being said

- Anticipating what is being said and thus never actually listening

- Contemplating their response while the speaker is talking

- Having personal issues or outside distractors compete with the message

- Reacting emotionally and thus missing the entire message.

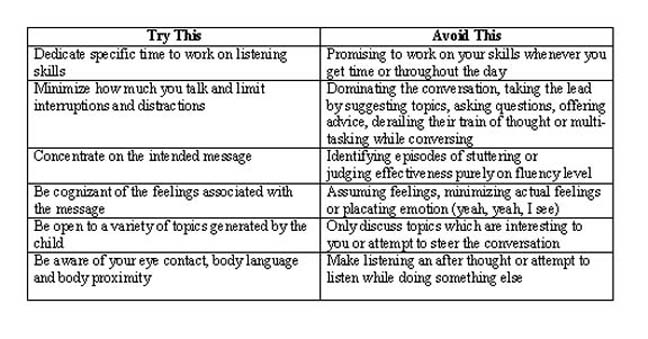

Below you will find a quick reference chart that can serve as a reminder of how to increase your listening skills.

The authors suggest that you incorporate the skills discussed in this paper into your everyday interactions and keep track of any changes. These changes may come in a variety of forms. Some parents report that their children are talking more, using longer utterances and sharing more personal information. Others report that their children are more willing to talk and initiating conversation more. Still other parents observe significantly less speech-related anxiety and some report that their children are actually stuttering less while communicating more.

References:

Faber, A., & Mazlish, E., (1999). How to talk so kids will listen and listen so kids will talk. 20th Anniversary Edition. New York: New York. Harper Collins Publishers.

Luterman, D., M., (2001). Counseling families with communication disorders and their families. Austin, Texas: Pro-Ed.

Manning, W. H., (2001). Clinical Decision Making in Fluency Disorders. Second Edition. San Diego, CA: Singular.

Neukrug, E, (1999). The world of the counselor: An introduction to the counseling profession. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Shapiro, D. (1999). Stuttering intervention: A collaborative journey to fluency freedom. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.