The Impact of Stuttering and Parental Involvement on Children and Teens

|

About the presenter: John A. Tetnowski, Ph.D., CCC-SLP, is the Ben Blanco Memorial Endowed Professor in Communicative Disorders at the University of Louisiana at Lafayette. He is a Board Recognized Fluency Specialist and Mentor. He has authored many articles on stuttering, and associated disorders, as well as papers on qualitative research and assessment procedures. He has treated people who stutter for over 15 years and was recently named the 2006 Outstanding Speech-Language Pathologist by the National Stuttering Association. |

|

About the presenter: Jim McClure is a person who stutters, a member of the National Stuttering Association's board of directors and the consumer representative on the Specialty Board on Fluency Disorders. He was a NSA chapter leader in Chicago for many years before relocating to Albuquerque, New Mexico. Jim is a fellow of the Public Relations Society of America and is a retired U.S. Navy public affairs officer. |

The Impact of Stuttering and Parental Involvement on Children and Teens

by John Tetnoski and Jim McClure,

from Louisiana and New Mexico, USA

Much of the evidence that exists about stuttering and stuttering therapy comes from objective measures of stuttering judged by speech-language pathologists (e.g., Ingham & Riley, 1998). Only recently, have researchers begun to systematically investigate the impact of stuttering on the lives of people who stutter (e.g., Yaruss & Quesal, 2006). In another line of research, some investigators have discovered the specific facets of therapy that lead to successful outcomes (Plexico, Manning & DiLollo, 2005). They found that a combination of therapist behaviors, support opportunities, and even some forms/types of therapies have a greater impact on what is deemed as a successful therapeutic outcome. The combination of these techniques has put the question of what constitutes a positive therapeutic outcome to the test.

In an attempt to gather more information about the impact of stuttering from a greater number of individuals, several surveys have been completed over the past several years (e.g., Yaruss et al., 2002). Some of these surveys have asked questions relating to the impact of self-help, the type of therapy viewed as successful, and clinician characteristics. Technological advances have made it even easier to survey larger numbers of people who stutter. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate the self perceptions on several issues related to stuttering and therapeutic impact for people who stutter. The results discussed in this paper will be the preliminary results of a survey of children who stutter, teens who stutter, and their parents.

Methods

The online survey was conducted by the NSA and Friends between October 2010 and January 2011. Parents of children who stutter, and teens and young adults who stutter, were invited to participate via the NSA and Friends email lists. The survey also was promoted to speech-language pathologists via the Specialty Board on Fluency Disorders and ASHA Special Interest Group 4. 253 parents and 205 teens responded to the survey.

Results

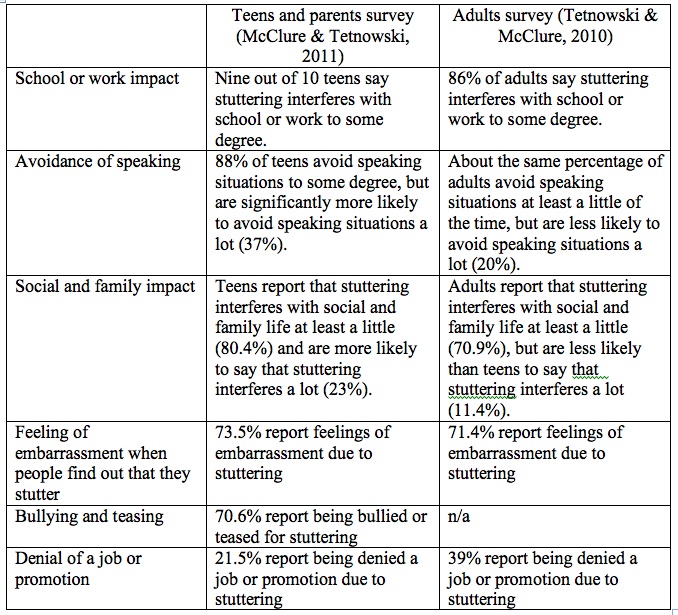

Life impact of stuttering (teens and adults)

The results of the teens survey indicate several trends and in some cases are compared to survey results of an earlier survey directed solely at adults (Tetnowski & McClure, 2010).

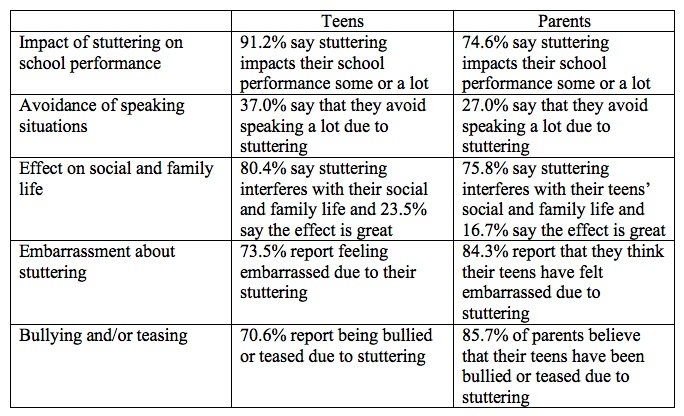

Comparison of teens and parents responses

Parents may underestimate the impact stuttering has on the lives of children and teens. The table below highlights some of the major differences between the responses of parents of teens and the teens themselves.

Trends from parents of young children (pre-school)

Only a handful of parents of pre-school children who stutter (n = xx) responded to the survey. The parents of children who stutter (age 5-12) report the following: 61.3% of parents say stuttering interferes with their children's school (versus 91.2% for teens), 58% say stuttering interferes with their children's family and social life (versus 80.4% for teens), 67.9% say that their children avoid speaking situations (vs. 85.2% of teens), 76.4% say that their children are embarrassed about their stuttering (vs. 84.3% of teens) and 63.1% report that their children have been bullied or teased about stuttering (vs. 85.7% of teens).

Overall results from parents regarding school-age children who stutter and teens who stutter

Additionally, 56% of parents report that someone else in their family stutters, and 20% said their children had been diagnosed with another developmental disorder (e.g., ADD or autism spectrum disorder, and others). Also, 14% of parents say they had been advised to defer speech therapy for their children by a pediatrician or physician and 6.1% received this advice from a speech therapist. Sadly, 14.7% were denied access to speech therapy in school.

Parental involvement in therapy

The survey also looked at general trends related to speech therapy for their children. An overwhelming majority of parents reported participating in conferences with their children's speech therapists (92.9%). However, fewer parents report making changes in the speaking environment at home (78.7%), working with their children on speech homework assignments (65.3%), observing (57.3%) or participating in therapy sessions (45.5%), or learning to conduct therapy sessions at home (54.1%).

Discussion:

The results of this survey indicate that children and teens do indeed have a difficult time in many typical social situations. Earlier research by Hayhow, Cray, & Enderby (2002) and Langevin (2009) has suggested that children and teens who stutter may indeed have difficulty with issues such as forming peer relationships, taking part in group discussions, difficulty in classroom discussions and other educational activities, and even report having low self-esteem related to education. Furthermore, the differences between the feelings that the teens have themselves and the inconsistencies with their parental attitudes, bears notice when treating teens who stutter.

This survey suggests that the involvement of some parents is limited and is at its lowest level during the teenage years, when the impact of stuttering may potentially be the greatest.

Future studies should explore the extent of parental involvement in their children's speech therapy and the impact this may have on therapeutic outcomes.

References:

Hayhow, R., Cray, A.M. & Enderby, P. (2002). Stammering and therapy views of people who stammer. Jounal of Fluency Disorders. 27, 1-17.

Ingham, J.C., & Riley, G. (1998). Guidelines for documentation of treatment efficacy for young children who stutter. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 41, 753-770.

Langevin, M. (2009). The peer attitudes towards children who stutter scale: Reliability, known groups validity, and negativity of elementary school-age children's attitudes. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 34, 72-86.

Plexico, L., Manning, W.H., & DiLollo, A. (2005). A phenomenological understanding of successful stuttering management. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 30, ( 1), 1-22.

Tetnowski, J.A. & McClure, J. (2010). Experiences of people who stutter: National Stuttering Association 2009 survey. Poster presentation at the Annual Conference of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Philadelphia, PA.

Yaruss, J.S., & Quesal, R. (2006). Overall assessment of the speaking experiences of stuttering (OASES): Documenting multiple outcomes in stuttering treatment. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 31, 90-115.