Using Fictional Literature as a Tool in Fluency Intervention Programs for Children and Teens

|

About the presenter: Kelly Jones, M.A., CCC-SLP works as a speech-language pathologist in a pediatric private practice in Chapel Hill, NC. She received a Master's degree in Speech-Language Pathology from the University of Florida. |

|

About the presenter: Kenneth Logan, Ph.D., CCC/SLP is a member of the Department of Communication Sciences and Disorders at the University of Florida, where he teaches, conducts research, and supervises clinical activities related to fluency disorders. He has presented many papers and authored a number of articles that deal with the nature and treatment of stuttering. |

Using fictional literature as a tool in fluency intervention programs for children and teens

by Kelly Jones and Kenneth Logan

from North Carolina and Florida, USA

The purpose of this paper is to describe how juvenile fiction (i.e., fictional stories that are written for children and teens) can be used as a tool within the context of a comprehensive stuttering management program. Juvenile fiction has been used with a variety of clinical populations (cf. Lyneham & Rapee, 2006; McKendree-Smith, Floyd & Scogin, 2003; Shechtman, 1999); however, its use in the treatment of stuttering, to date, appears to be limited. The application of fictional stories to therapeutic settings has been termed bibliotherapy. In its broadest form, bibliotherapy refers to the sharing of books or stories for the purpose of helping a person gain insight about and/or deal with a personal problem (Heath, Sheen, Leavy, Young, & Money, 2005). Forgan (2002) listed several motivations for using bibliotherapy in therapy settings. These include: showing an individual that others have encountered the same problem, helping an individual to discuss his or her problems more freely, improving an individual's self-concept, and helping an individual to develop constructive solutions to the problems they face. Many authors have presented bibliotherapy as a self-contained approach to intervention. Because stuttering is a multi-dimensional problem (Logan & Yaruss, 1999; Murphy, Yaruss, & Quesal, 2007), however, we think it is preferable for clinicians to regard these book-based activities as but one of many resources that a clinician can use to address treatment goals.

A variety of studies have examined the effects of bibliotherapy and other forms of directed reading on patients' functioning. Directed reading programs that use professionally-authored manuals/texts have been found to improve functioning for depressed and anxious patients (Lyneham & Rapee, 2006; McKendree-Smith, Floyd, & Scogin, 2003). Also, activities derived from juvenile fiction books have been linked to improvements in students' self-concept ratings (Lenkowsky et al. 1987) and use of insightful and self-disclosure statements (Shechtman, 1999). Other studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of bibliotherapy in promoting exploration of personal attitudes, feelings, and emotions with other populations of children, including adopted children, children of divorce, and children with a diminished self-concept (Heath et al., 2005).

The depiction of stuttering in juvenile fiction

Since the 1960's, over 50 juvenile fiction books featuring characters who stutter have been published. Such books are potentially useful in the treatment of stuttering because they provide a venue for exploring the various ways that people experience, react to, and cope with stuttering. Logan, Mullins, and Jones (2008) reviewed the depiction of stuttering in 29 juvenile fiction books that were published between 1989 and 2007. The books encompassed a variety of literary styles (e.g., fantasy, fable, realistic fiction) and the reading levels ranged from early elementary school through young adult. Logan et al. noted that many of the books provided detailed accounts of stuttered speech and its impact on daily life. Depictions of teasing, bullying, and other listener reactions were common, and several books provided poignant accounts of the attitudes, feelings, and emotions that can accompany chronic stuttering. In general, books that were written for older readers addressed stuttering in much greater depth than books that were written for younger readers.

With many of the books in the Logan et al. (2008) review, a character's challenges with stuttering coincided with other problems, e.g., dealing with the loss of or separation from a parent, struggling to gain social acceptance from peer groups. Only 4 of the 29 books depicted scenes from speech therapy sessions; yet, nearly all of the books included examples of accomplishments that the characters had made in communication and/or general life activities. Logan et al. concluded that most of the 29 books would be suitable for use in stuttering therapy activities, particularly activities that are designed to (1) build children's background knowledge about stuttering; (2) validate children's stuttering-related experiences; (3) promote children's willingness to disclose their experiences with stuttering to others; and (4) develop more effective ways to manage stuttering, respond to listener reactions, and cope with feelings and emotions.

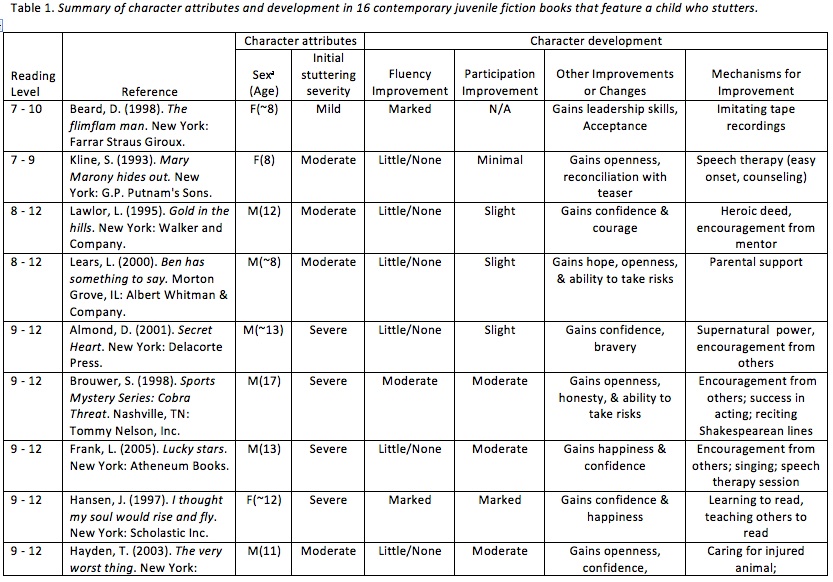

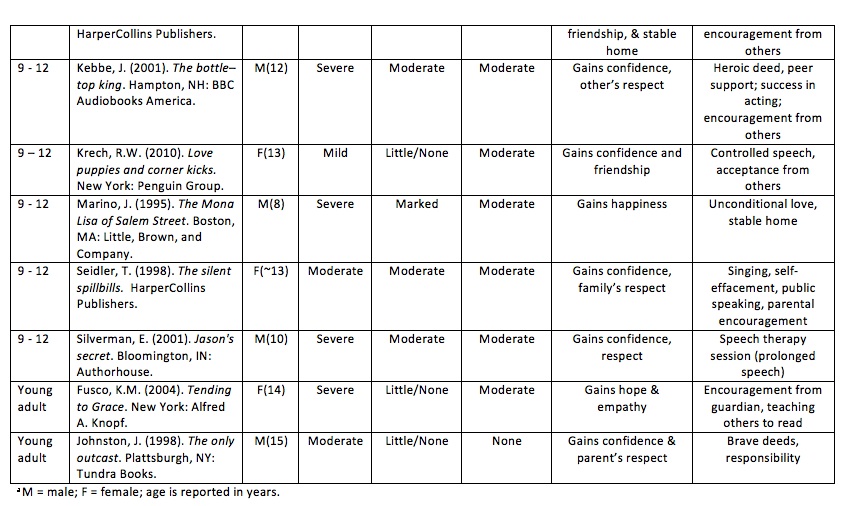

General attributes about the characters in 16 contemporary juvenile fiction books (organized by reading level and author) are presented in Table 1. The listed books are by no means an exhaustive review of stuttering-related juvenile fiction books nor are they necessarily recommended for use with all children who stutter. It is essential that a clinician read a book carefully before using it in a therapy activity, to determine what situations, if any, are applicable to their particular client(s). Additional details about these and other stories can be found in the following sources: Bushey and Martin (1988), Logan et al. (2008), and the Stuttering Homepage.

As can be seen, the books in Table 1 (at the end of the article) feature both male and female characters and a variety of ages and severity levels. Each of the books features examples of stuttered speech and the ways in which stuttering symptoms vary across contexts. All but one of the books (The Flimflam Man) addresses the attitudes, feelings, and emotions that commonly accompany stuttering. Several of the books also provide descriptions of coping strategies (e.g., word substitution, situational avoidance) and listener behaviors (e.g., bullying, interrupting) that often aggravate stuttering. Generally, the books are successful at promoting hopefulness in the reader, as each of the characters makes some type of positive change (though not necessarily improved speech fluency) during the course of the story.

Example of a treatment activity

It has been suggested that children respond best to bibliotherapy when it is based upon a story that has personal meaning for the student (Heath et al., 2005; Silverman, 2004). Thus, clinicians should consider a client's age, gender, background, personality, and unique personal challenges when selecting a book to use in a fluency therapy activity.

The recently published book Love Puppies and Corner Kicks, by R.W. Krech, is examined here with regard to its potential use within an intervention program for a child who stutters. The book tells the story of a 13-year-old girl named Andrea who stutters. Andrea moves with her family to Scotland for a year and must deal with the challenges of making friends in a new school and new country while addressing her speech difficulties. Andrea begins at her new school pretending to have laryngitis so she won't be called upon. She finds acceptance from the other students through her talent for playing soccer, but finds it hard to talk to a boy she likes because she is afraid she might stutter. Andrea tries to hide her stuttering from her classmates and the boy throughout the story, but realizes at the end that her friends are not concerned about whether or not she stutters.

Children who stutter often experience negative attitudes, beliefs, and emotions as a consequence of their difficulties with communication (Logan & Yaruss, 1999; Murphy et al., 2007). A stuttering intervention activity that utilizes Love Puppies and Corner Kicks to address such issues might proceed by using the following 4-step process, adapted from Forgan, 2002, to create a suitable activity.

- Pre-reading: The first step is pre-reading, wherein the child who stutters is asked to draw upon her background knowledge of the topic to predict what will happen in the story. The clinician could begin the pre-reading activity by saying the following: "This story is about a girl who moves to a new country and tries to make friends. She often has trouble speaking smoothly to others because she stutters. How do you think this will affect her?" Prior to posing this question to the child, it would be helpful for the clinician to help the child who stutters develop a basic understanding of speech production and what constitutes stuttering.

- Guided reading: The term guided reading refers to a situation where the clinician and client read a story together and, while doing so, the clinician poses questions that direct the client to consider particular concepts or possibilities. Because this book is 213 pages long, it would not be feasible to read the entire story during therapy time. Accordingly, the client could be asked to read the book in stages at home (e.g., "Read pages 1 to 100 in the next two weeks") and to come to the therapy session prepared to discuss the assigned portions. With this approach, the clinician could then use therapy time to conduct guided reading activities that deal with specific sections of the book. The following excerpt, which describes Andrea's experience with being called upon to read aloud on her first day at a new school, would be a good passage to use.

"'Andrea? How about you start?' After reading the excerpt, the clinician could then ask the child who stutters to write a journal entry that relates to the situation. The clinician could say, "Andrea had trouble reading aloud in class. Write a paragraph or two in your journal about a situation you have faced where you had difficulty talking or tried to hide your stuttering." (For clients who are uncomfortable with discussing their personal experiences, the writing prompt could be altered slightly so that the journal entry could be written from the character's perspective.)'Gak'-- A noise emerges from my throat. I was trying to say something and not say something at the same time, and 'gak' came out. I look like a total fool! But--Wait! Brainstorm! I point at my throat and shake my head no.

Mrs. Watkinson gets it. 'Oh no! You have laryngitis on the first day?!' I nod vigorously and make sad puppy eyes.

'Oh, bad luck. Well, I'll introduce you. Class, this is Andrea DiLorenzo from New Jersey in America. Welcome, Andrea.'

I give a half-smile and nod. My heart is still racing. I can feel the blood in my temples. I'm relieved but also ashamed that I chickened out so quickly." (p. 40)

- Post-reading discussion: During this stage, the client and the clinician could work together to discuss Andrea's communication problems. At this time, a discussion of "thinking traps" from a cognitive-behavioral perspective would be beneficial (see Manning, 2010, pp. 320-39 for an overview of cognitive-behavioral principles). Some examples of thinking traps Andrea falls into include: all or nothing thinking (if her speech is not perfect, then the interaction is a complete failure), mind reading (assuming what others will think about her speech), and mental filter (dwelling on negative situations rather than moving on). It would also be appropriate at this time to encourage the client to identify when and why Andrea falls into these traps, the pros and cons associated with thinking traps, and why it is difficult for Andrea to avoid the thinking traps. As the client addresses these issues, the clinician should then assess the client's readiness for discussing her own experiences with thinking traps. When conducting this activity, it is important to remind the client that challenging situations occur routinely in everyday life and that everyone is subject to them.

- Problem solving: In the final stage of the activity, the clinician could ask the client to describe and then evaluate how Andrea addressed her stuttering-related challenges. Andrea's actions could be evaluated in terms of both their drawbacks and benefits. For example, from the excerpt above, the client and clinician could discuss the pros and cons of Andrea's laryngitis hoax. The clinician could then ask the client how she has acted in similar situations (e.g., "Have you ever tried to hide your stuttering from others?"). The role of thinking traps in the laryngitis hoax (and the client's personal attempts to conceal stuttering) could then be discussed (see previous step), along with an evaluation of the positive and negative consequences of these actions and thought patterns. The clinician and client could then conclude the activity by brainstorming more constructive ways to act and think in such situations. The clinician and client could then collaborate to create an action plan wherein the client identifies specific situations in the upcoming week in which she intends to change how she responds to stuttering challenges.

Measuring Outcomes

Options for documenting progress and measuring outcomes with book-based activities are numerous. The selected approach will depend largely on the goals associated with a particular activity. Heath et al (2005) described a five-part framework that is well suited for documenting evidence of attitude change during the course of book-based activities. With this approach, the clinician would collect information about the number and nature of statements made in the following areas during the course of an activity:

- Involvement (e.g., general remarks about stuttering-related experiences of book characters or self; depth and breadth of participation in stuttering-related discussions )

- Identification (e.g., statements that convey an awareness of similarities in the life situations of the character and client)

- Catharsis (e.g., statements that reflect recognition of and/or vicarious experience of the character's feelings)

- Insight (e.g., statements that reflect analysis of story events and how those events might be applied to the client's own life)

- Universalism (e.g., statements that indicate an awareness of the personal challenges that other people face and the ways in which one's own challenges relate to those of others).

A complete discussion of outcomes assessment is beyond the scope of this article; however, the basic approach is to document changes in the quantity and quality of stuttering-related statements that a client makes within and beyond the therapy setting, and if possible, to relate such changes to the client's communication performance in activities that are associated with clinical action plans (see "Problem solving" in the previous section) as well as routine daily activities.

Conclusions

The many examples of stuttering-related experiences in juvenile fiction books offer clinicians a context for helping children to build their knowledge of stuttering, validate and explore their communicative experiences, and expand their repertoire of stuttering management strategies. There are many contemporary books that are available to clinicians for this purpose. Although book-based activities will usually constitute just one aspect of a multi-pronged approach to stuttering treatment, the open-ended nature of such activities allows for their use in activities that address a wide range of clinical goals.

References

Bushey, T., & Martin, R. (1988). Stuttering in children's literature. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 19, 235-250.

Forgan, J.W. (2002). Using bibliotherapy to teach problem solving. Intervention in School and Clinic, 38, 75-82.

Heath, M.A., Sheen, D., Leavy, D., Young, E., & Money, K. (2005). Bibliotherapy: A resource to facilitate emotional healing and growth. School Psychology International, 26, 563-580.

Lenkowsky, R.S., Barowsky, E.I., Dayboch, M., Puccio, L., & Lenkowsky, B.E. (1987). Effects of bibliotherapy on the self-concept of learning disabled, emotionally handicapped adolescents in a classroom setting. Psychological Reports, 61, 483-488.

Logan, K.J., Mullins, M.S., & Jones, K.M. (2008). The depiction of stuttering in contemporary juvenile fiction: Implications for clinical practice. Psychology in the Schools, 45, 609-626.

Logan, K.J., & Yaruss, J.S. (1999). Helping parents address attitudinal and emotional factors with young children who stutter. Contemporary issues in Communication Science and Disorders, 26, 69-81.

Lyneham, H.J. & Rapee, R.M. (2006). Evaluation of therapist-supported parent implemented CBT for anxiety disorders in rural children. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1287-1300.

Manning, W.H. (2010). Clinical decision making in fluency disorders (3rd ed.). Clifton Park, NY: Delmar.

McKendree-Smith, N.L., Floyd, M., & Scogin, F.M. (2003). Self-administered treatments for depression: A review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 275-288.

Murphy, W.P., Yaruss, J.S., & Quesal, R.W. (2007). Enhancing treatment for school-age children who stutter I. Reducing negative reactions through desensitization and cognitive restructuring. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 32, 121-138.

Shechtman, Z. (1999). Bibliotherapy: An indirect approach to treatment of childhood aggression. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 30, 39-53.

Silverman, E.M. (2004, October). Using story to help heal. Paper presented at the International Stuttering Awareness Day Online Conference. Retrieved July 17, 2010, from http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/isad7/papers/silverman7.html