Stuttering and Social Phobia (Social Anxiety Disorder): Background Information and Clinical Implications

|

About the presenter: Larry Molt is chair of the Department of Communication Disorders and the director of the Neuroprocesses Research Laboratory at Auburn University. He holds a dual masters degree in speech-language pathology and audiology from the University of South Florida and Ph.D. in speech and hearing science from the University of Tennessee. Larry is ASHA certified in both fields and is an ASHA Board-Recognized Fluency Specialist. He serves on the executive board of the International Fluency Association, and as coordinator of Special Interest Division 4 (Fluency & Fluency Disorders) of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. Larry was named 2003 Speech-Language Pathologist of the Year by the National Stuttering Association. His current research involves EEG topographic mapping of brain activity in a variety of speech, language and auditory disorders, with a prominent interest in stuttering. A person who stutters himself, he entered the field of speech-language pathology in search of a more efficacious approach to treating stuttering. |

Stuttering and Social Phobia (Social Anxiety Disorder): Background Information and Clinical Implications

by Larry Molt

from Alabama, USA

Anxiety has almost invariably been suggested as either a necessary or at least as an accompanying component of stuttering. Direct research into the role of anxiety in stuttering has been carried on for over sixty years. But defining the presence of anxiety in individuals who stutter and the relationship and role of anxiety to stuttering has been difficult and confusing. Anxiety has been suggested as playing a primary role in a variety of theories, from neurosis/psychosis models ( e.g., Glauber, 1958), learned behavior (e.g., Moore, 1938), and physiologic/multifactorial models (e.g., Smith & Kelly, ). Many authors describe a clear role for anxiety in the development and/or maintenance of stuttering and provide empirical evidence of heightened anxiety levels in people who stutter, Conversely, others dispute the necessity of anxiety in the equation and cite empirical research demonstrating no difference in measures of anxiety between stutterers and nonstutterers. Discrepancies among research studies in the type of anxiety examined (e. g., general /trait anxiety, vs. situation specific/state anxiety) and measurement techniques (personality inventories, self-report scales, physiologic indicies such as cardiovascular or electrodermal responses, or cortisol levels in saliva, etc.) further add to the discrepant and confusing results seen in the literature.

Perhaps nowhere in recent years has the relationship between anxiety and stuttering seemed more confusing than when discussing social phobia (social anxiety disorders) and linkages to stuttering. From clinical definitions to treatment implications, controversy abounds. Participants in support groups and internet discussion forums sometimes tout the effectiveness and importance of pharmaceutical treatment of social phobia in reducing stuttering frequency and encouraging participation in conversational situations. Others report no benefit from pharmaceutical treatments or even suggest increased disfluency, depression, or discomfort. Many cognitive and behavioral treatment approaches employed in stuttering therapy mirror approaches used in treating social phobia (desensitization, challenging belief systems, and hierarchial insertion into various speaking situations) and often deal with anxiety surrounding social communication. This legitimately leads to the question "what is actually being manipulated within some forms of fluency therapy - stuttering or social anxiety?" The purpose of this article to provide the reader with background information defining social phobia, discuss the controversy regarding its relationship with stuttering, and review some of the limited empirical evidence available both regarding the relationship and how treatment of social phobia symptoms affects stuttering patterns.

Defining Social Phobia

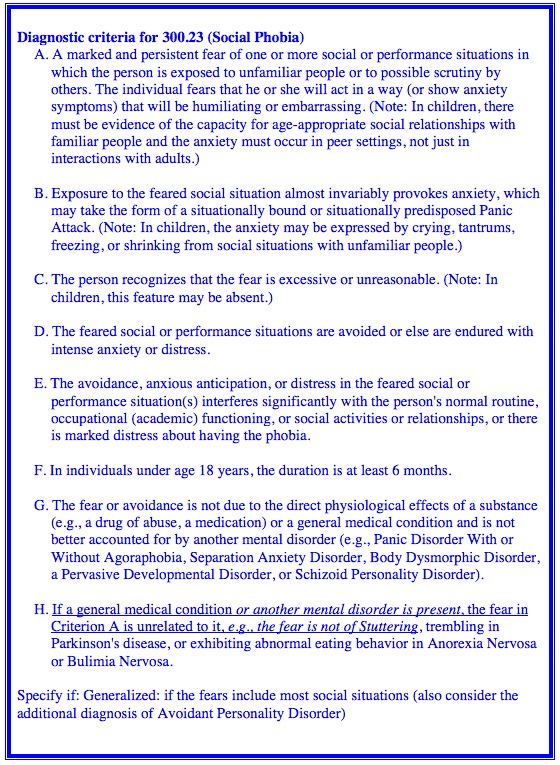

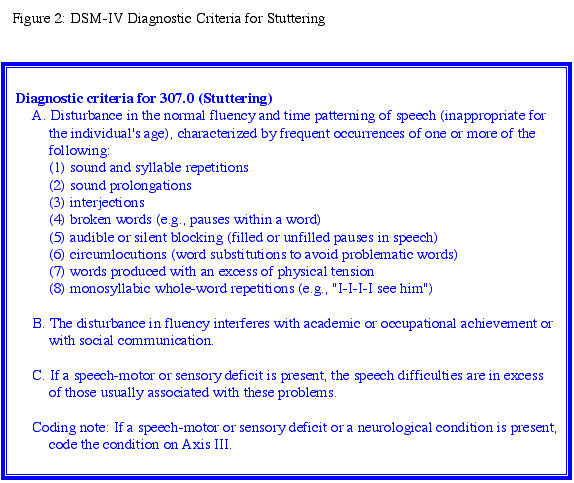

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is the standard classification of mental disorders used by professionals in the health and mental health professions in the United States. The present version, DSM-IV, was published in1994 and a more recent update, DSM-IV-TR (with minor descriptive revisions/Text Revisions) was released in 2000. The DSM-IV provides a set of diagnostic criteria and descriptive information that indicate what symptoms must be present, and for how long (known as inclusion criteria) in order to qualify for a diagnosis of a particular disorder. Also included are those symptoms that must not be present (i. e., exclusion criteria) in order for an individual to qualify for a particular diagnosis. The DSM classification system includes diagnostic codes derived from the coding system used by health care professionals in the United States, known as the ICD-9-CM. The DSM-IV provides the currently accepted diagnostic criteria for social phobia (ICD-9 code number 300.23) and for stuttering (ICD-9 code number 307.0). Part of the confusion regarding the relationship of the two disorders begins in the inclusion and exclusion criteria for social phobia as well as in the descriptive criteria for stuttering. There is also some confusion between the use of the term social phobia and social anxiety disorder, especially in the lay literature. The DSM-IV Taskforce on Anxiety Disorders recommends use of the DSM III and IV term "social phobia", but suggested that social anxiety disorder be considered as an acceptable alternative name for social phobia.

The fact that stuttering is listed in the DSM-IV leads some speech-language pathologists and consumers to believe that health professionals thereby consider it a mental disorder. It is important to note, however, that it is listed under the area "disorders usually diagnosed in infancy, childhood, or adolescence". This area includes mental retardation, reading disorders, learning disorders, motor skill disorders, Tourette's syndrome, autism, and several other communication disorders, including phonological disorders and various forms of language disorders.

The DSM provides a general classification system for disorders, known as the axis system, with five primary categories. These consists of: Axis I (clinical disorders and conditions that need clinical attention), Axis II (personality disorders), Axis III (general medical conditions), Axis IV (life events/psychosocial and environmental problems), and Axis V (global assessment of functioning scale/the "numerical" level at which a person functions). Both stuttering and social phobia are considered as Axis I disorders, which includes many conditions and disorders that are marked by organic underpinnings but that may also have psychological components. Social phobia in the DSM-IV is viewed within a framework of other anxiety disorders. The DSM-IV provides diagnostic criteria for acute stress disorder, agoraphobia without history of panic disorder, anxiety disorder due to general medical condition, generalized anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder with agoraphobia, panic disorder without agoraphobia, posttraumatic stress disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, and substance-induced anxiety disorder.

Figures 1 & 2 provide a listing of the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for social phobia and for stuttering. There are two important statements in the diagnostic criteria for the two disorders. For stutterng, criteria B states: the disturbance in fluency interferes with academic or occupational achievement or with social communication. For social phobia, criteria H indicates: If a general medical condition or another mental disorder is present, the fear in Criterion A is unrelated to it, e.g., the fear is not of Stuttering, trembling in Parkinson's disease, or exhibiting abnormal eating behavior in Anorexia Nervosa or Bulimia Nervosa. (italics provided by author). The diagnostic criteria for stuttering recognizes, as inclusion criteria, that the stuttering (disturbance in fluency) may likely interfere with social communication. Because difficulty in social communication is an accepted criteria of stuttering, consequently, for social phobia, the presence of stuttering becomes an exclusion criteria), If social phobia is to be a comorbid diagnosis when stuttering (or some other medical condition/mental disorder) is also present, the fear/phobia must not be fear of stuttering (or fear of the other disorder).

It is helpful to examine the DSM-IV "descriptive text" for social phobia for further clarification:

"In feared social or performance situations, individuals with Social Phobia experience concerns about embarrassment and are afraid that others will judge them to be anxious, weak, "crazy," or stupid. They may fear public speaking because of concern that others will notice their trembling hands or voice or they may experience extreme anxiety when conversing with others because of fear that they will appear inarticulate. They may fear public speaking because of concern that others will notice their trembling hands or voice or they may experience extreme anxiety when conversing with others because of a fear of being embarrassed by having others see their hands shake. Individuals with Social Phobia almost always experience symptoms of anxiety (e.g., palpitations, tremors, sweating, gastrointestinal discomfort, diarrhea, muscle tension, blushing, confusion) in the feared social situations, and, in severe cases, these symptoms may meet the criteria for a Panic Attack. Blushing may be more typical of Social Phobia."

"Adults with Social Phobia recognize that the fear is excessive or unreasonable, although this is not always the case in children. For example, the diagnosis would be Delusional Disorder instead of Social Phobia for an individual who avoids eating in public because of a conviction that he or she will be observed by the police and who does not recognize that this fear is excessive and unreasonable. Moreover, the diagnosis should not be given if the fear is reasonable given the context of the stimuli (e.g., fear of being called on in class when unprepared)."

"The person with Social Phobia will typically avoid the feared situations. Less commonly, the person forces himself or herself to endure the social or performance situation, but experiences it with intense anxiety. Marked anticipatory anxiety may also occur far in advance of upcoming social or public situations (e.g., worrying every day for several weeks before attending a social event). There may be a vicious cycle of anticipatory anxiety leading to fearful cognition and anxiety symptoms in the feared situation, which leads to actual or perceived poor performance in the feared situations, which leads to embarrassment and increased anticipatory anxiety about the feared situations and so on."

"The fear or avoidance must interfere significantly with the person's normal routine, occupational or academic functioning, or social activities and relationships, or the person must experience marked distress about having the phobia. For example, a person who is afraid of speaking in public would not receive a diagnosis of Social Phobia if this activity is not routinely encountered on the job or in the classroom and the person is not particularly distressed about it. Fears of being embarrassed in social situations is common, but usually the degree of distress or impairment is insufficient to warrant a diagnosis of Social Phobia. Transient social anxiety is especially common in childhood and adolescence (e.g., an adolescent girl may avoid eating in front of boys for a short time, then resume normal behavior). In those younger than 18 years, only symptoms that persist for at least 6 months qualify for the diagnosis of Social Phobia."

"Additional Specifier: "Generalized" can be used when the fears are related to most social situations (e.g., initiating or maintaining conversations, participating in small groups, dating, speaking to authority figures, attending parties). Individuals with Social Phobia, Generalized, usually fear both public performance situations and social interactional situations. Individuals who do not meet the definition of Generalized compose a heterogeneous group that includes persons who fear a single performance situation as well as those who fear several, but not most, social situations. Individuals with Social Phobia, Generalized, may be more likely to manifest deficits in social skills and to have severe social and work impairment."

Is the Presence of Social Phobia Typical in People Who Stutter?

Anyone familiar with stuttering can identify multiple descriptions in the criteria for social phobia listed above that are common in the individual who stutters: anticipatory anxiety before the event, avoidance, anxiety during the situation, and embarrassment during and following the situation. The DSM-IV criteria differentiates between the two when the anxiety/discomfort results "merely" from the stuttering, rather than the social situation itself (Mahr & Torosian, 1999). Theoretically, if the stuttering was not present (or at least not an issue), the individual would not experience abnormal anxiety levels towards social communication situations. Social phobics fear the situation itself; stutterers fear the appearance of stuttering within the situation, and are aware which situations put them more at risk. The differentiation is important. If anxiety towards social communication is inherent in stuttering because of the abnormality of the speech disfluencies, what purpose would it serve to also diagnose it as a second disorder, social phobia, implying a fear of social communication and situations in general, if that generalized fear is not present. But is it really that simple to differentiate?

There is a considerable amount of research indicating that people who stutter in general do not differ as a group from normally speaking individuals on measures of general anxiety (nonsituational-specific anxiety). See Bloodstein (1995) for a comprehensive review of anxiety research. Many argue, however, that there may be at least a subset of individuals who stutter who do have unacceptably high levels of discomfort towards social situations, irregardless of whether or not stuttering occurs. Several studies (George & Lydiard,1994; DeCarle & Pato, 1996; Stein, Baird, & Walker, 1996, Schneier, Wexler, & Liebowitz, 1997; Kraaimaat, Vanryckeghem, & van Dam-Baggen, 2002) have compared various anxiety measures in groups of stuttering individuals to those acquired from socially phobic individuals and reported in general to find similar results, at least for a portion of the stuttering group. That also agrees with some of the research comparing the performance of people who stutter to that of normally fluent individuals on measures examining differences in anxiety specific to communication activities and/or measures of communication apprehension (Craig, 1990; Miller & Watson, 1993; Blood, Blood, Tellis, & Gabel, 2001; Gabel, Colcord, & Petrosino, 2002). Such studies often report that stutterers as a group exhibit significantly more anxiety towards speaking/communication situations than nonstutterers. Not all would agree that differences in anxiety levels between stutterers and nonstutterers supports a diagnosis of social phobia. Mahr & Torosian (1999) report stutterers to be more anxious than normally speaking control group participants, but clearly less anxious than the members of a group of social phobic individuals, on a battery of self-report measures of anxiety.

Unfortunately, the literature review outcome remains somewhat muddled at this point, for the majority of research doesn't necessarily successfully differentiate between social phobia and stuttering-specific anxiety. Some differentiate between fear of stuttering vs fear of social communication via self-report measures. Structuring the way that questions are asked may assist in differentiating between various forms of anxiety, but content validity of the measures is difficult to determine. Attempts at validating paper and pencil measures with physiologic measures of anxiety have been successful at times, but not at others. Blood, Blood, Bennett & Simpson (1994) reported differences between stutterers and nonstutterers facing low, medium and high stress situations in salivary cortisol levels, but not on self-report measures of anxiety. Dietrich & Roaman (2001) reported significant differences between the groups on self-report measures, but the measures were not substantiated by electrodemal (skin conductance) measures. Other researchers attempt to limit the diagnosis of comorbid social phobia and stuttering to individuals whose social anxiety was clearly excessive in relation to the severity of stuttering (Stein, Baird, & Walker, 1996). This is an interesting approach and may carry implications for considering the role social phobia may play for some individuals considered to be "covert" stutterers.

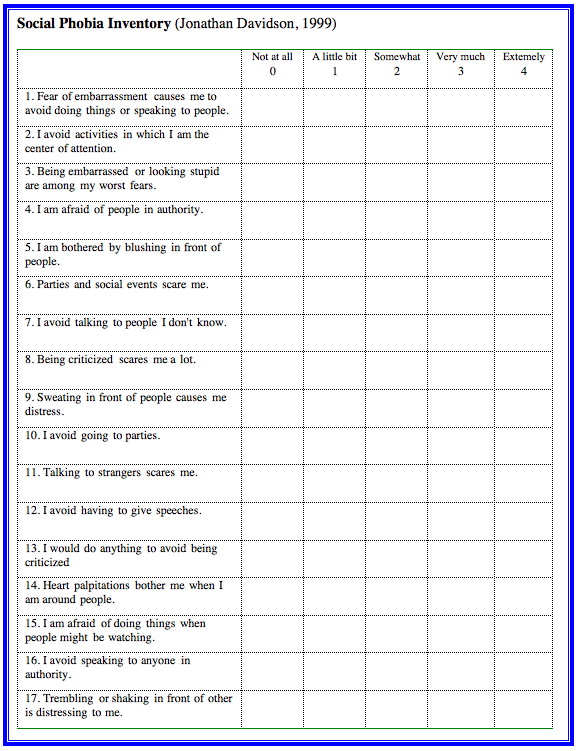

To allow the reader to better understand some of the diagnostic features associated with social phobia and how they differ from a typical stuttering inventory, an example of a social phobia inventory (SPIN) is presented in Figure 3. The Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN) was developed by Dr. Jonathan Davidson at Duke University (Connor, Davidson, Churchill, Sherwood, Foa, & Weisler, 2000). Scores of 19 or greater are thought to be sufficient for a diagnosis of social phobia. Dr. Davidson reports that individuals typically presenting themselves for therapeutic assistance would have a score of 40 or higher on the Spin (68 points is the maximum possible score).

What are we left with? At least some stutterers do experience high levels of anxiety towards social communication that may mirror, at least in depth or strength, feelings seen in individuals with social phobias. Prevalence figures for social phobia exceed those seen for stuttering, so one could argue that as the two disorders do not appear to be mutually exclusive conditions, social phobia could be expected in some stuttering individuals. {Note: Epidemiological and community-based studies have reported a lifetime prevalence of social phobia ranging from 3% to 13% (Moutier & Stein, 1999). The reported prevalence may vary due to differences in the threshold used to determine distress or impairment, the nature of the instruments or measures, and the number of types of social situations specifically surveyed. In one study, 20% of respondents reported excessive fear of public speaking and performance, but only about 2% appeared to experience enough impairment or distress to warrant a diagnosis of Social Phobia.} Additionally, due to the fact that the two share several common symptom patterns, it is not unreasonable to expect that some stutterers experience comorbid social phobia. The current research base does not support, however, the contention of a widespread relationship between the two disorders.

The issue of differentiating between individuals who exhibit stuttering with comorbid social phobia vs. those without the comorbid disorder remains important, for it may have implications for success in therapy or in possible reasons for relapse, if the comorbid anxiety disorder remains untreated. Even differentiating between individuals experiencing high anxiety levels vs. low anxiety levels towards social communication situations (whether they are linked to stuttering or a more generalized social phobia) is equally important, for those same reasons.

One final comment in this domain. The concern about differentiating between social phobia and fear of a particular disorder occurring or interfering with social interaction extends beyond stuttering. George and Lydiard (1994) called for research examining social phobia-like symptoms observed in individuals with benign essential tremor (BET) and other physical disabilities.

Therapy for Social Phobia vs Therapy for Stuttering

A variety of approaches have been utilized for treating social phobia. These include psychological counseling and/or psychoanalysis, hypnosis, relaxation, behavioral therapy, cognitive therapy, and pharmacotherapy (Moutier & Stein, 1999; Van Ameringen, Mancini, Farvolden,& Oakman, 2000). Those same approaches have also been tried with stuttering (Bloodstein, 1995). What is important to consider is the similarity of therapeutic management techniques across the two disorders. Because of the similarity of the disorders and many of the symptoms, successful strategies for one may have implications for the other.

Behavioral approaches for treating social phobia emphasize elimination/reduction of avoidance behaviors. They generally utilize a hierarchially-arranged exposure to the fear-triggering stimuli (e. g., social situations) very similar to the situational hierarchies often employed in fluency therapy. Visualization and/or role playing is often used for situations that may be difficult to arrange in real-life. Cognitive approaches are also employed. Patients are encouraged to challenge faulty thoughts and beliefs that help to maintain the disorder. Identification and monitoring of inappropriate beliefs or thoughts, refuting the thoughts and employing coping techniques are common activities. Again these are similar to techniques utilized in some fluency therapy approaches. A recent article by Spurr and Stopa (2003) examined the negative effect of utilizing the "observer perspective". They reported that social phobics often generated a negative impression of how they appear to others, constructed from their own thoughts, feelings, and internal sensations. Such a pattern appears similar to that employed by some stutterers. The authors discussed implications of such a viewpoint in negatively regulating behaviors.

Pharmacotherapy most often involves the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), with Paxil (paroxetine) and Zoloft (sertraline) popular choices. Other SSRIs used in managing social anxiety include Celexa (citalopram), Prozac (fluoxetine), and Luvox (fluvoxamine). The FDA has also approved Effexor XR (venlafaxine), a serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) for social phobia treatment. Other drugs that may be used include the benzodiazepines (BDZs) such as Xanax (alprazolam), Klonopin (clonazepam), and Valium (diazepam). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are thought to play a role in increasing available serotonin (by inhibiting the enzyme responsible for degrading serotonin and norepinephrine) and have been used. Finally, Neurontin (gabapentine), an antiepileptic, and the heart-regulating beta-andrenergic receptor blocking agents (beta-blockers), such as Inderal (propranolol), are occassionally used.

Neurobiology of Social Phobia vs. Stuttering

Not surprisingly, (especially given the similarity of some symptoms) both disorders appear likely to share some similar neurobiological substrates. The success of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) in pharmacological management of social phobia at this point is considered to indicate a probable role for a disturbance in serotonergic functioning in social phobia. Similar success has been observed for the monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) that are thought to play a role in increasing available serotonin. There have been limited reports of significant reduction in the frequency of stuttering for individuals receiving treatment with SSRIs (Oberlander, Schneier,& Liebowitz,1993; Costa & Kroll, 1996; Muray & Newman, 1997; Brady & Zahir, 2000) and MAOIs (Heimberg, Liebowitz, Hope, Schneier, Holt, & Welkowits,1998). The effectiveness of the serotonergic agents for treating stuttering, however, are much more variable than seen with social phobia, and are often based on single subject reports.

Other research has identified possible dopamine disturbances in both disorders. A much higher incidence of social phobia has been noted in individuals with Parkinson's disease (Richard, Schiffer, & Kurlan, 1996), a disorder of dopamine metabolism and production. Neuroimaging research using dopamine sensitive transporting agents have indicated differences in dopamine D2 receptor activity in various basal gangliar structures in individuals with social phobia (Tiihonen, Kuikka, & Bergstrom,1997; Schneier, Liebowitz,& Abi-Dargham, 2000). Gerry Maguire and his colleagues at the University of California-Irvine have reported differences in D2 receptor activity in the corpus striatum of individuals who stutter (Wu, Maguire, Riley, Lee, Keator, & Tang, 1997; Maguire, Gottschalk, Riley, Franklin, Bechtel, & Ashurst, 1999).

The functions of other neurotransmitters and neuromodulators have been examined regarding social phobia and/or stuttering. These include norepinephrine, corticotrophin releasing factor (CRF), cholesystokinin, and gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA). While the research is limited in these areas, some promising leads seem to be appearing.

Recent research has also identified possible differences in the caudate, putamen, cingulate gyrus and amygdala function in social phobic individuals (see Van Ameringen, Mancini, Farvolden, & Oakman, 2000, for a review of the neurobiology of social phobia and Rauch, Shin, & Wright, 2003 for research on amygdala function). Several of those structures have also been implicated in stuttering. See Costa & Kroll (2000) for a fairly recent summary article dealing with neurobiological issues in stuttering, and Daryl Dodge's website: http://telosnet.com/dmdodge/veils/index.html for a discussion of the possible role of the amygdala.

At first glance, the variety of neurobiological differences that have been reported appears confusing. The body's arousal and anxiety response system, however, is managed by several different systems, including the brainstem (cardiovascular and respiratory responses), limbic system (mood and anxiety responses), prefrontal cortex (responsible for risk/danger appraisals), and the motor cortex. A variety of neurotransmitters and neuromodulators each play roles in the management and regulation of those areas. Depending on the nature of a neurobiological dysfunction in the arousal/anxiety response system, it would not be unreasonable to see differences across a variety of neurochemical agents or across a variety of functional structures within a particular regulatory system

References

American Psychiatric Association (1994). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fourth Edition (DSM-IV).

American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders - Fourth Edition - Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR).

Blood, G. W., Blood, I. M., Tellis, G., & Gabel, R. (2001). Communication apprehension and self-perceived communication competence in adolescents who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 26, 161-178.

Blood, G. W., Blood, I. M., Bennett, S., & Simpson, K. C. (1994). Subjective anxiety measurements and cortisol responses in adults who stutter. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research, 37(4), 760-768.

Bloodstein, O. (1995). A Handbook on Stuttering (5th Edition) . San Diego: Singular Press.

Brady, J. P. & Ali, Z. (2000). Alprazolam, citalopram, and clomipramine for stuttering. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacy, 20(2), 287.

Craig, A. (1990). An investigation into the relationship between anxiety and stuttering. Journal of Speech & Hearing Disorders, 55(2), 290-294.

Connor, K. M., Davidson, J. R., Churchill, L. E., Sherwood, A., Foa, E., & Weisler, R. H. (2000). Psychometric properties of the Social Phobia Inventory (SPIN). British Journal of Psychiatry, 176, 379-386.

Costa, A. D. & Kroll, R. M. (2000). Stuttering: An update for physicians. Canadian Medical Association Journal,162(13), 1849-1855.

Costa, A. D. & Kroll, R. M. (1996). Sertraline in stuttering. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacy,15(6), 443-444.

De Carle, J. A. & Pato, M. T. (1996). Social phobia and stuttering. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(10), 1367-1368.

Dietrich, S. & Roaman, M. H. (2001). Physiologic arousal and predictions of anxiety by people who stutter. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 26, 207-225.

Gabel, R. M., Colcord, R. D. & Petrosino, L. (2002). Self-reported anxiety of adults who do and do not stutter. Perceptual and motor Skills, 94(3), 775-784.

George, M. S. & Lydiard, R. B. (1994). Social phobia secondary to physical disability. A review of benign essential tremor (BET) and stuttering. Psychosomatics, 35(6), 520-523.

Glauber, I. P. (1938). The psychoanalysis of stuttering. In Eisenson, J. (ed.) Stuttering: A symposium. New York: Harper and Row.

Heimberg, R. J., Liebowitz, M. R., Hope, D. A., Schneier, F. R., Holt, C. S. & Welkowits, L. A. (1998). Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. phenelezine therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 1133-1141.

Kessler, R. C., Stein, M. B., & Berglund, P. (1998). Social phobia subtypes in the National Comorbidity Survey. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 155(5), 613-619

Kraaimaat, F. W., Vanryckeghem, M., & van Dam-Baggen, R. (2002). Stuttering and social anxiety. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 27, 319-331.

Kraaimaat, F. W., Janssen, P., & van Dam-Baggen, R. (2002). Social anxiety and stuttering. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 72, 766.

Lapin, I. (2003). Phenibut (Beta-phenyl-GABA): A tranquilizer and nootropic drug. CNS Drug Reviews, 7(4), 471-481.

Maguire, G. A., Gottschalk, L. A., Riley, G. D., Franklin, D. L., Bechtel, R. J., & Ashurst, J. (1999). Stuttering: Neuropsychiatric features measured by content analysis of speech and the effect of risperidone on stuttering severity. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 40(4), 308-314.

Mahr, G. C. & Torosian, T. (1999). Anxiety and social phobia in stuttering. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 24, 119-126.

Miller, S. & Watson, B. C. (1993). The relationship between communication attitude, anxiety, and depression in stutterers and nonstutterers. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research, 35(4), 789-798.

Moore, W. E. (1938). A conditioned reflex study of stuttering. Journal of Speech Disorders, 3,163-183.

Moutier, C. Y. & Stein, M. B. (1999). The history, epidemiology, and differential diagnosis of social anxiety disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 60, 4-8.

Murray, M. G. & Newman, R. M. (1997). Paroxetine for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorders and comorbid stuttering. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(7), 1037.

Oberlander, E., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1993). Treatment of stuttering with phenelzine. American Journal of Psychiatry, 150(2), 355.

Rauch, S. L., Shin, L. M., & Wright, C. I. (2003). Neuroimaging studies of amygdala function in anxiety disorders. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 985, 389-410.

Richard, I. H., Schiffer, R. B., & Kurlan, R. (1996). Anxiety and Parkinson's disease. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 8, 383-392.

Schneier, F. R., Liebowitz, M. R., & Abi-Dargham, A. (2000). Low dopamine D2 receptor binding potential in social phobia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 157, 457-459.

Schneier, F. R., Wexler, K. B., & Liebowitz, M. R. (1997). Social phobia and stuttering. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154(1), 131.

Smith, A. & Kelly, E. (1998). Stuttering: A dynamic, multifactorial model. In R. Curlee & G. M. Siegel (eds.) Nature and Treatment of Stuttering: New Directions. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Spurr, J. M. & Stopa, L. (2003). The observer perspective: Effects on social anxiety and performance. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41, 1009-1028.

Stein, M. B., Baird, A. M., & Walker, J. R. (1996). Social phobia in adults with stuttering. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 153(2), 278-280.

Tiihonen, J., Kuikka, J., & Bergstrom, K. (1997). Dopamine reuptake densities in patients with soicial phobia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 154, 239-242.

Van Ameringen, M., Mancini, C., Farvolden, P., & Oakman, J. (2000). The neurobiology of social phobia: From pharmacotherapy to brain imaging. Current Psychiatric reports, 2, 358-366.

Wu, J. C., Maguire, G., Riley, G., Lee, A., Keator, D., & Tang, C. (1997). Increased dopamine activity associated with stuttering. Neuroreport, 10, 767-770.

September 30, 2003