Charles Van Riper: His Curse Became His Acclaim

The following article appeared in Encore, a magazine published in Kalamazoo, Michigan, January 1990. It is printed below with the permission of the author.

Charles Van Riper: His Curse Became His Acclaim

By Tom Thinnes

An often painful and tormented childhood as a severe stutterer energized him into becoming one of the world's most renowned researchers and pioneers in speech pathology.

In the history of any university is a president, coach, or faculty member who helped put the institution on the map, who gave it an identity, a reputation, a standard of excellence for others to follow.

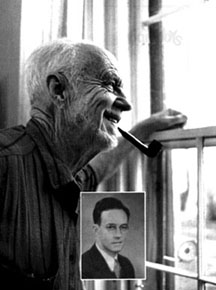

Such a legendary figure for Western Michigan University is Charles Van Riper, now 84 years old and the teller of Upper Peninsula tales as author Cully Gage. An often painful and tormented childhood as a severe stutterer energized him into becoming one of the world's most renowned researchers and pioneers in speech pathology. A native of Champion in ~ Michigan's upper level, Van Riper came to the Western campus in 1936 and established the first speech clinic in the state.

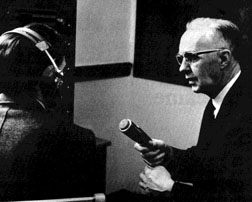

During his four-decades-plus at Western and even after his 1976 retirement as a Distinguished University Professor, Van Riper spread the word around the globe about the campus's capabilities in speech pathology and audiology. When the WMU Board of Trustees decided to establish a department of speech pathology and audiology in 1965, it was a no-doubter who would head it up. The speech, hearing, and language clinic in that department now bears Van Riper's name, thanks to WMU Board action in May of 1983.

Not too shabby an achievement for a man who was such an embarrassment to his family because of his stuttering that he occasionally was not allowed to eat at the table when guests were invited into the home.

"As a boy, I was a very severe stutterer," says Van Riper, gazing out at a homemade version of the Upper Peninsula on his West Milham Road acreage. "I had awful blockings, struggling so badly that I looked like an epileptic. Trying to get a word out, I'd jerk and twitch and have all kinds of spasms. People would slap me across the face to get me out of it. They had the idea that it was some kind of dirty habit, almost like oral masturbation. The attitudes of society toward people with speech defects were crude back then. Their treatment was reprehensible when compared to today's standards.

"You just weren't supposed to stutter," says Van Riper, who has been widowed for about five years. "If you did stutter, you were some kind of freak. You were evil, and thus susceptible to punishments and penalties. That's why I went out to the woods a lot, to be myself and to be by myself. There were fears that I would never be able to speak."

Van Riper says he never really experienced any kind of adolescence because of his speech problems. Talking and expressing opinions as open and free as the Michigan woods that he loves as Cully Gage, Van Riper said it was hard for him as a professional speech pathologist to work with adolescents. "I just couldn't understand them. I had a hard time with my own kids [two daughters and a son], too."

Van Riper says he never really experienced any kind of adolescence because of his speech problems. Talking and expressing opinions as open and free as the Michigan woods that he loves as Cully Gage, Van Riper said it was hard for him as a professional speech pathologist to work with adolescents. "I just couldn't understand them. I had a hard time with my own kids [two daughters and a son], too."

Trying to get a word out, I'd jerk and twitch and have all kinds of spasms.

But, in retrospect, that nightmare was the best thing that ever happened to Van Riper. The cliches fit nicely in his story - always darkest before the dawn, turning a problem into a challenge and opportunity. "I evolved out of it," he says. "I learned how to size them up. If I was able to change and become comfortable with my stuttering, then they certainly were, too. If I had faith in them, then they had to have faith in themselves. If I could become successful, so could they. As therapy, it was very, very successful.

"Of course, all of this had a great impact on me as well," Van Riper says. "There is great satisfaction in being able to do something good in your life. I think I have impacted on the lives of many for the better. That's my greatest accomplishment and the most important value in my life."

The son of an Upper Peninsula physician, Van Riper did not overcome the handicap of being a severe stutterer until he was 26. By that time, he had demonstrated enough innate intelligence to gain entrance into Northern Michigan University, complete two years, and then go on to the University of Michigan to complete a bachelor's degree in physics and English.

He wrote the first textbook of its kind in the nation on speech pathology.

"When, at the age of 26," Van Riper wrote in one of his scores of books, articles, and research articles, "I first attained enough fluency to join the human race, I decided to design a life plan so that the rest of my existence would be better than that I had known previously. Those first 26 years had been full of misery and frustration. The rest would be lived as well as I could possibly manage them.

"Now that I could communicate and no longer had to constantly spend my energies in the anxieties and strugglings of severe stuttering," the passage continued, "all things were possible. I would make that ugly life of mine a shining thing."

By 1930, he had a master's degree from the Ann Arbor campus. Heading west, Van Riper settled at the University of Iowa to earn a doctorate in psychology, to work with his own speech, and to associate with many of the pioneers in the speech-pathology field. In 1936, the same year that Kalamazoo beckoned, he married the former Catharine Jane Hall, the daughter of an Iowa physician and the first speech-pathology major to graduate from the University of Iowa's undergraduate program.

How did this son of Champion become a champion in his field in Kalamazoo?

First and foremost, he was spurred by the passion that, as far as he was concerned, nobody should have to go through the hell that he did as a child. Once he had conquered his stuttering, Van Riper cloaked himself in a missionary zeal to help others overcome problems in expressing themselves verbally. The challenge was that speech pathology back in those days was a nearly uncultivated field and Van Riper had to become one of the pioneers who did the plowing.

First and foremost, he was spurred by the passion that, as far as he was concerned, nobody should have to go through the hell that he did as a child. Once he had conquered his stuttering, Van Riper cloaked himself in a missionary zeal to help others overcome problems in expressing themselves verbally. The challenge was that speech pathology back in those days was a nearly uncultivated field and Van Riper had to become one of the pioneers who did the plowing.

"I didn't have any background in speech pathology because hardly anybody did," he said in recalling those early days. "So I became a psychologist because I thought that was about as close as I could come in terms of academic discipline. I had to learn about speech pathology as I went along."

In the process, Van Riper wrote the first textbook of its kind in the nation and established the first clinic in Michigan, which also happened to be only the fourth such institution in the country. The latter required a lot of lobbying with state legislators in Lansing.

"I got the job in Kalamazoo because of Paul Sangren, who had just become president of what was then known as the Normal School at Western," Van Riper says. "Sangren had a nephew who stuttered badly. His nephew had been put through the same crud that I had been as a youngster. Back then, there was no real help for kids like myself and Paul's nephew. I was sent to some quack institutions, just as he had - fraudulent ones."

In such places, Van Riper says, "the trainers would try to teach you to speak to a rhythm. Wave the arm and say the word with each swing of the arm. There were lots of other tricks like that. As far as speech therapy was concerned, tricks were all they had back then and they were pure garbage. After I had learned the hard way, I decided that I might be able to stutter more easily."

That became the Van Riper technique - instead of trying to eradicate the habit of stuttering, try to learn techniques in which you stutter more easily and thus hardly noticeably.

"You stutter more easily when you refuse to struggle at the moment," he explains. "The person who stutters has little lags in his speech. Some of them are so tiny that the average listener can't distinguish them. As a child, I felt those lags, panicked, lost control, and they became a very long, severe stutter. That's when I began to jerk my head, jump around, and gasp. So I learned to stutter more easily, almost naturally."

Whether it was mind over matter or his intense desire to end being the Van Riper family embarrassment, he learned the technique.

"At any rate, Paul Sangren knew about the quack institutions and understood the devastation that stuttering can do to a person," Van Riper says. "He wanted to establish a reputable, scientifically based speech clinic, which was relatively unheard of in those days. He advertised, I heard about the opportunity, and here I am.

Today, it is a profession. There are more than 60,000 members in the American Speech and Hearing Association. "Of course, it wasn't all Charlie Van Riper, but I had a part in it," he says. "There aren't many people who can say that they built a profession, especially a profession that has changed the attitudes of society toward the handicapped, particularly toward the person who stutters. It is now accepted as a problem that can be corrected. To me, that's a major accomplishment."

Part of the normal life that he promised himself was an 80-acre retreat which frequently became an outreach of the campus clinic. Over the years, he and his wife brought student-patients, some with social problems that far outstripped their speech difficulties, into their West Milham Road home. The "Earth Mother," as he called his late wife Catherine, "was able to heal them much better than I did. She loved and babied them. She understood them." Catherine also practiced her profession outside of the home, serving as a psychologist and therapist at the Child Guidance Clinic for many years. "His name is Bill Wensley. Combat during World War II greatly affected him, so much so that he was admitted to a psychiatric unit in Battle Creek. Prone to fighting, Bill also had a very severe stuttering problem. Because he frequently escaped and raised hell in Battle Creek, they took away his pants.

To be brutally truthful, it was terrible at first because I had little support.

They couldn't control him. An incorrigible. Catherine said 'Let's bring him home.' They thought we were nuts. Why would we want a berserk guy running around our house?

"Our children were accustomed to having people who stuttered in our home because they knew these were people I had trouble helping in the clinic setting. At first, it was difficult putting up with Bill's outbursts, but we persevered.

"Our children were accustomed to having people who stuttered in our home because they knew these were people I had trouble helping in the clinic setting. At first, it was difficult putting up with Bill's outbursts, but we persevered.

"After a short time, it became clear. Bill had outbursts because of frustration and those frustrations were based on his inability to speak clearly. Stuttering was the core of his misbehavior, the reason he went mad."

Van Riper charted a course of treatment that included both physical and mental components. While he taught the technique of stuttering more easily, Van Riper also prescribed some physical labor to relieve Bill's frustrations. The task was to build an outside fireplace and Bill tackled the chore with great zeal.

"He went out into the back 40 and found the largest rocks he could," Van Riper says. "He lugged and rolled them in. Some were three feet in diameter. And he began to build something. As his frustrations eased, so did the stuttering. He learned how to stutter easily. As the fireplace grew, so did his confidence. He was free from the shackles of a speech defect."

And there is a happy ending to the real-life script. Bill Wensley went on to follow in the footsteps of his mentors and became a speech pathologist. Armed with a master's degree, Bill established a speech clinic of his own on the west coast and is now retired in Alaska. "He helped a lot of people and did an awful lot of good," says the proud teacher.

The fireplace fits in nicely with Van Riper's red-brick farmhouse, which was built in 1859 and was the first of its kind in the area. The builder was a fellow named Steven Howard, who was one of the Kalamazoo area's first settlers in the early 1830s. A local physician also called it home for a spell. During the Civil War, Union supporters gathered there to raise funds for the cause and buy long underwear for the troops. The Van Ripers assumed ownership about a half-century ago.

The fireplace fits in nicely with Van Riper's red-brick farmhouse, which was built in 1859 and was the first of its kind in the area. The builder was a fellow named Steven Howard, who was one of the Kalamazoo area's first settlers in the early 1830s. A local physician also called it home for a spell. During the Civil War, Union supporters gathered there to raise funds for the cause and buy long underwear for the troops. The Van Ripers assumed ownership about a half-century ago.

In the old basement, Doctor Van, or Cully, as his friends call him, has wine. Digging around in an old chest of drawers down there, he found a skull that had a small hole behind the ear. An anthropologist told Van Riper that the skull was that of an Indian girl, around 18 years old at the time of death.

"She either died from a mastoid infection or was hit by an arrow behind the ear," Van Riper says. "I think all old houses should have a skeleton in its closet. I at least got a part of one."

Van Riper bought the property for $14,000, an investment that he recouped when he granted an easement to Consumer's Power Company. Even though vehicles by the thousands stream by each day on nearby I-94, there is still enough natural serenity to satisfy Van Riper, at least until he can travel to his real Shangri-La in the Upper Peninsula. "I've got two gardens down here," he says, "and a fountain. That stand of trees out there is my link to the Upper Peninsula. I planted most of them, 300 or so. Hardwoods. Oaks and maples. The pines are now nearly 50 feet tall. This is my own cocoon. I can sit out in those woods, light up my pipe, and philosophize. The healing of myself starts in those woods, or when surrounded by great bouquets of flowers in the garden. Bathed in beauty, it's easy to be happy."

I can become part of it all. I'm young again. I 'm sipping from the Fountain of Youth.

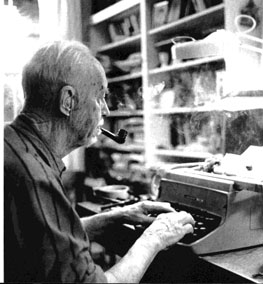

Van Riper can watch cascading water bubble up from a fountain made from an old kettle once used to scald hogs. Maybe he can hear the vegetables grow in his second garden. "I'll sit down there in the early morning or evening and watch the wildlife come in - the deer, raccoons, possum, squirrels. Even with the cars flying by beyond the soybean field, I can become part of it all. I'm young again. I'm sipping from the Fountain of Youth. I take that feeling back to my typewriter."

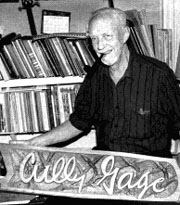

And out pops Cully Gage! And tales of his real-life Shangri-La, the Upper Peninsula, to which he travels each summer. "I renew my boyhood up there amidst the moose, the deer, the wolves, and the loons on the lake. I can go for 40 miles and never hit a road. That's where I bathe my soul." Cully comes from Kalle, the Finnish word for Charles. Gage is the maiden name of Van Riper's mother.

And out pops Cully Gage! And tales of his real-life Shangri-La, the Upper Peninsula, to which he travels each summer. "I renew my boyhood up there amidst the moose, the deer, the wolves, and the loons on the lake. I can go for 40 miles and never hit a road. That's where I bathe my soul." Cully comes from Kalle, the Finnish word for Charles. Gage is the maiden name of Van Riper's mother.

His first effort was The Northwoods Reader, a book of stories about true-life characters he had known as a boy growing up in Champion. The volume was seasoned by a few tales that he "just made up." The intent was to write for his children and grandchildren so that they could know how things truly were in the Upper Peninsula around the turn of the century. He showed the tales to close friends, who recommended that he submit the volume to a publisher. A publishing firm in the Upper Peninsula went for it.

The name Cully Gage seemed to fit this change-of-pace in writing. After all, Charles Van Riper was the author of scholarly research papers and textbooks. Charles Van Riper had to be careful about what he said. Cully Gage could freewheel. And he sure did!

"The books were easy to write. I'd get a vague idea of a tale, do some mulling over it, try to find in my memories some character who would fit in, and then the stuff just poured out of my index fingers," he says.

His first editor was the "Earth Mother." If Catharine, his wife, didn't chuckle or get teary-eyed, he'd go back to the drawing board and do some revising. "It turned out I didn't have any worries about being sued," he says. "The people up there loved the tales. The feedback was great and that drove me to keep on writing them. I've written seven volumes in the Northwoods series now. Some have called me the Garrison Keillor of the Upper Peninsula. Except I have Van Riper Lakes instead of Woebegone."

I love you, Cully Gage, because you have always been so in love with life.

As Dean Martin used to say, keep those cards and letter coming, folks, because they are therapeutic for Cully Gage, who has had more than his share of ambulance runs. There have also been bouts with diabetes.

"I've written about 35 books," he says, "but I enjoy the Cully Gages the most." So do many of his readers, if his mail is any indication:

"Your stories put me in a place I wish I was," wrote one reader. "They soothe the soul."

A younger fan wrote: "I'm not much of a speller, but your stories touch my hart and warm my soal."

"I could not quit reading until I snapped the last page closed," said another. "Aw, Cully, you broke my poor cracked old heart again and I love you for it. Here's to you, old sir, with all my gratitude, respect, and a dual clink of the glass and my old deutsch head. Good stuff! Goddammit, Cully, I mean it."

"I laughed and I cried," wrote one emotional reader. "What a great satisfaction it must be to bring joy to so many people. I hope that we will have more stories from you before you join your beloved Grandpa Gage."

"I laughed and I cried," wrote one emotional reader. "What a great satisfaction it must be to bring joy to so many people. I hope that we will have more stories from you before you join your beloved Grandpa Gage."

"I love you, Cully Gage, because you have always been so in love with life," wrote an elderly woman "I treasure your books. Thank you for writing them and sharing your heart's ease with me. What a beautiful, kindred person you are!"

A Love Affair with the U.P. was not in the genre of the other Northwood Readers. For Cully Gage, this book was more of a "gut check," as athletes like to say when times are the most tense in the contest. Instead of telling tales about the fascinating characters he knew as a boy, he talked about the land, the forests, the lakes, and the streams of the Upper Peninsula, and how they shaped one man's life. Chapters were titled "My Boyhood in the Forest," "The Dark Years of My Youth," and "Living Alone in the Forest."

The last chapter on "Growing Old" dealt with the death of his beloved "Earth Mother" after two years of chemotherapy for cancer. Here's the concluding paragraphs:

"This book should probably end right here, but there is just a bit more to say. In September, my son, John, drove me up to the lakes to do some of my grieving. Some of it. My healing rock didn't help much and after I got home, I found our old house very, very empty.

"But life goes on, a life that has a big hole in it which shows no sign of shrinking, but I try to live around it with some grace. Writing more Northwood Readers has helped and so have my trips northward. I've managed to get to the cabins every summer and every deer season. Everything up there has changed; yet everything remains the same. Herman sits on his white rock; the old cabin holds me in its arms; the forests and lakes lift my spirit. Children and grandchildren join me there and last summer at the cabin on the second lake, we watched a mother moose feeding on Katy's [his wife] white water lilies, then swim with her calf across to the south shore. The loons give their long wail at eventide and I find some peace. That other love affair, the one I've had with my beloved U.P., still continues. I'll be back again, old cabin."

Van Riper's classic textbooks in speech pathology have been translated into German, French, Finnish, Spanish, Japanese, Korean, and Arabic. There is even a Braille version. Thanks to Van Riper's leadership and the growth of the WMU department to international stature, students from all over the world come to Kalamazoo to train in the profession of speech pathology.

"But it has been my little books about the people I knew as a boy in the Upper Peninsula that have given me the greatest pleasure," Van Riper says. "They have evidently rung a small gong and I get a lot of fan mail which tells me about other lives and experiences up there. My readers have sent me smoked fish, pasties, saffron bread, maple syrup, and other U.P. specialties. People just drop by the old farm here and visit. Old men don't usually make new friends, but these books have brought many to me."

"Old men don't usually make new friends, but these books have brought many to me. "

Parents and friends of children, who have seen how his definitive texts - The Nature of Stuttering and The Treatment of Stuttering - have improved their young lives and freed them from the shackles of a speech defect, probably do not agree with this assessment of the value of his written words. Cully Gage brings happiness and warm memories. Charles Van Riper perhaps brought hope.

In his 627-page volume on The Nature of Stuttering, Van Riper surveyed the world literature on the subject, compiling and organizing most of the information concerning the nature and the cause of the disorder. The book contains essentially everything from the first written mention of stuttering to the latest concepts in French, Japanese, Russian, Hungarian, Polish, German, and English. Van Riper examined all written accounts from before the time of Christ to the present, providing a wealth of clinical observations and experiences. It has become a classic.

His books on Teaching Your Child to Talk and on Speech in the Elementary Classroom were among the accomplishments that brought him the highest award that the American Speech and Hearing Association can bestow upon a professional. In honor of his status as a distinguished professor emeritus, the WMU department established an annual Van Riper lecture series, which is now in its ninth year, and gave its speech clinic his name.

Van Riper eventually returned the favor to President Sangren, with whom he became closely associated both professionally and socially over the years' They were hunting partners, especially when the quarry was pheasant. Sangren himself used Van Riper's talents later in life when Parkinson's disease slurred the WMU president's speech.

"Today," Van Riper says, "the WMU Department of Speech Pathology is know all over the world. It's famous because it's a good one. It didn't matter one iota when I left. They were able to keep it going at top speed and I am very proud of that."

As Cully Gage, Van Riper understands a man's relationship with his environment, with nature's way. From that exudes his sense of serenity, of being part of it all. A sense of humor helps as well.

"I have this huge shredding machine," Van Riper says. "I use it to compost corn stalks, leaves, and other vegetation. One day, it got stuck. Before trying to fix it, you are told to unhook the spark-plug wire to avoid accidents. Then it's safe to remove what is plugging up the shredder. Well, I didn't do that and, all of a sudden, the blades started to revolve.

"I looked down into the bin and saw the scarlet and green colors. The green was from the corn stalks. I didn't know where the red came from. I just said, 'My, isn't that beautiful!' Hell, then I realized those were my fingers. I wrapped my hand in a towel and off I went to the hospital to get sewed up.

"When I got back to the farm," he says, "I continued with the composting, finger stubs and all. I put the results on the roses. I think I'm the only man who ever was reincarnated as a rose and lived to see it. I recycled myself. The roses that year had the biggest blooms I ever saw." Kind of blood red!

"I'm not afraid of death. It will be the end of a useful life. "

"Because of my health problems and the loss of my wife," Van Riper says, "it's been hard to maintain that sense of serenity, but I've managed. I'm not afraid of death. It will be the end of a useful life. I made a very fine life after a very evil beginning. I became a useful person and had an impact for good. I think I have helped a lot of people. So I have a right to feel some peace. The problems of my childhood are just memories, something to learn from.

Van Riper could have harbored lifetime ill feelings against his father, but if he once did they are long forgotten and buried. "My feeling of rejection was overwhelming. My father was a good man. I even wrote his biography to honor him. He was a wilderness physician who was adored by the people he treated and served. He accomplished much in his life, but he was very hard on his family and leaned hardest on me as the oldest child. I caught the brunt of his wrath because I was the one who should have known better. He experimented on me and I was just the victim of his mistakes as a new parent. Anyway, I forgave him a long time ago, but I don't know if he ever forgave me for the stuttering child that I became."

Van Riper could have harbored lifetime ill feelings against his father, but if he once did they are long forgotten and buried. "My feeling of rejection was overwhelming. My father was a good man. I even wrote his biography to honor him. He was a wilderness physician who was adored by the people he treated and served. He accomplished much in his life, but he was very hard on his family and leaned hardest on me as the oldest child. I caught the brunt of his wrath because I was the one who should have known better. He experimented on me and I was just the victim of his mistakes as a new parent. Anyway, I forgave him a long time ago, but I don't know if he ever forgave me for the stuttering child that I became."

From that evolved Dr. Charles Van Riper, a man of compassion and tremendous drive to help others.

"It would be enough if I had been able to help only one poor soul have a small moment of relief from the feeling of helplessness and frustration in stuttering," he says. "I know the glory of being able to reclaim a membership in the human race and to enjoy that birthright of being a human being, which is the gift of speech. When you don't have speech, you are pretty helpless and alone in the world."

added with permission of author

September 7, 1997