Recollections From A Pioneer

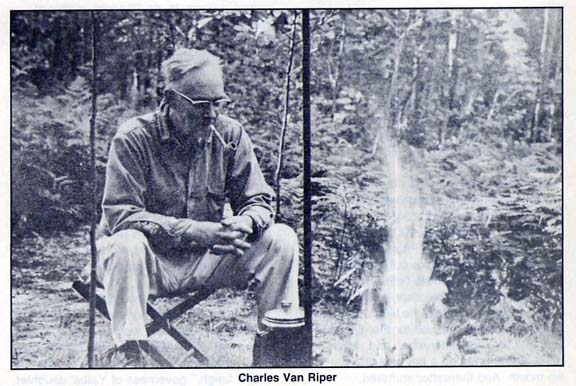

by Charles Van Riper

Charles Van Riper, founder and former chair of the Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology at Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, author of numerous textbooks on speech-language pathology, is also known as Cully Gage, author of the Northwoods Reader, folksy talkes about life in the Northwoods.

In the little forest village where I was born and raised we had a black tomcat who, in the course of his nine lives, changed the color of our cat population from gray to black. In my own single lifetime I have witnessed changes in our profession that are quite as remarkable. What other profession has changed its sex? When I entered our field our membership was predominantly male and look at it now. Again. what other profession has made such spectacular gains in membership? In 1930 there were only 28 other members and my annual dues were only $5.

Even our names have changed. AASC to ASSDS to ASCA to ASHA for our organization, and speech therapists. speech correctionists. speech clinicians, speech-language pathologists, audiologists, and speech scientists as our identifying roles. Our founding fathers used none of the latter titles. They viewed themselves as an elite group of academic scholars. They weren't particularly interested in therapy: they just wanted to understand the nature of those puzzling human disorders, especially stuttering. Meeting to exchange ideas and theories and to share their research findings. they were a tiny but closely knit group.

Fortunately, among them we also had some founding mothers--Mabel Gifford, Pauline Camp, Eudora Estabrook, Sara Stinchfield--speech teachers who were already offering remedial services in the schools. These women. together with some of us who stuttered (C.S. Bluemel, Sam Robbins, Wendell Johnson, and I) and who had been victimized by the quacks of the day, insisted that treatment should also be emphasized. So in 1934 we became the American Speech Correction Association. This shift in purpose was strongly opposed. Indeed. when I listen to the voices of the past, all I hear are arguments.

One of those arguments concerned our affiliation and work setting. Many maintained that since we were now treating speech disorders we should affiliate with medicine as had the physical and occupational therapists. Not so, counseled Bluemel, Kenyon, and Blanton, the wise physicians among us. "You'll never be more than the lowest on the medical totem pole. Create your own independent profession by creating laboratories and speech clinics within the speech and psychology departments of your universities, then train your workers to serve in the public schools. Speech disorders are not diseases." So we did, but look at our work settings now!

Not so, counseled Bluemel, Kenyon, and Blanton, the wise physicians among us. "You'll never be more than the lowest on the medical totem pole. Create your own independent profession by creating laboratories and speech clinics within the speech and psychology departments of your universities, then train your workers to serve in the public schools. Speech disorders are not diseases." So we did, but look at our work settings now!

Our early publications contrast markedly with those of today. At first we had only the mimeographed copies of our convention proceedings as an outlet for our articles but in 1936 the Journal of Speech Disorders made its appearance under the editorship of G. Oscar Russell, a member of the old guard, who tried to use it to shape our profession back to its earlier image. For seven years he did his utmost to impose a pedantic nomenclature upon us--not lisping but sigmatism, not cleft palate speech but uranoscolalia. He failed but that little journal did much to hold us together and it improved markedly when Wendell Johnson succeeded him. Indeed. it even became interesting reading, which is more than one can say for current publications. Sometime you should read the 1947 article entitled "The Talking Frog of Marion County" describing how a laryngectomee used the critter as a sound source.

Subsequent editors, Grant Fairbanks and Gordon Peterson, then steered the journal away from its emphasis on clinical practice to become primarily a publication of research. When this change occurred many clinicians objected and to allay their concerns the Journal of Speech and Hearing Research came into being but, unfortunately for the bulk of our membership. the old journal remained much the same. Then came Asha and Language. Speech, and Hearing in the Schools, both valiant but only partly successful attempts to address the needs of clinicians confronting their clients. Some day we may yet have a publication that will serve their needs.

The governance of our Association today is a far cry from what it was in the early years. Without a National Office or a House of Delegates, life was simpler then. All the power was in the hands of the executive Council, which picked the officers by offering only a single nominee for each post and the slate was always elected unanimously at the business meeting. As a member of that elite Executive Council, I was once offered the presidency, it being my turn, but I refused the honor when my wife said that if I were fool enough to accept, she'd sit on my lap when I first presided. I've always been a lousy administrator and she knew it. Yes, things have changed -- or have they?

The governance of our Association today is a far cry from what it was in the early years. Without a National Office or a House of Delegates, life was simpler then. All the power was in the hands of the executive Council, which picked the officers by offering only a single nominee for each post and the slate was always elected unanimously at the business meeting. As a member of that elite Executive Council, I was once offered the presidency, it being my turn, but I refused the honor when my wife said that if I were fool enough to accept, she'd sit on my lap when I first presided. I've always been a lousy administrator and she knew it. Yes, things have changed -- or have they?

Certainly our standards for membership have changed for the better. Had it not been for the grandfather's clause I would not be writing this piece because I've never had a course in speech pathology. The closest I could come was to get a doctorate in clinical psychology but I'm sure I have enough practicum hours. Could I pass the examination? I'd probably have to read some books first, preferably some I haven't written.

Back then we had no texts, no tools. We recorded our clients' speech on wax phonograph cylinders. Our sound waves were scratched on a smoke kymograph drum. Using tuning forks of different frequencies, we calibrated hearing loss by marks on the office carpet. We had no standardized tests. Look at what we have now!

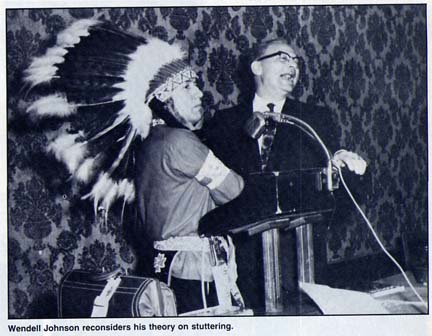

Though there has always been good talk and booze up in Mabel's room, our conventions have changed much over the years. I once did demonstration therapy on stage with a stuttering boy I'd never seen before. When Max Goldstein brought before us a plumber without a tongue who could speak intelligibly, we all had to look inside his mouth. When John Black brought his first DAF apparatus, we all had to try to talk without stuttering. When Wendell Johnson claimed that Indians didn't stutter because they had no word for it, we made sure that one in full was regalia would prance up the aisle stuttering between war whoops. We went to every session (there weren't many) and bedeviled the authors of presented papers with hungry or critical questions. We were a wild, unruly lot but we were close friends and fellow pioneers.

Though there has always been good talk and booze up in Mabel's room, our conventions have changed much over the years. I once did demonstration therapy on stage with a stuttering boy I'd never seen before. When Max Goldstein brought before us a plumber without a tongue who could speak intelligibly, we all had to look inside his mouth. When John Black brought his first DAF apparatus, we all had to try to talk without stuttering. When Wendell Johnson claimed that Indians didn't stutter because they had no word for it, we made sure that one in full was regalia would prance up the aisle stuttering between war whoops. We went to every session (there weren't many) and bedeviled the authors of presented papers with hungry or critical questions. We were a wild, unruly lot but we were close friends and fellow pioneers.

Have all these changes occurred without costs? Sadly, I say no. I feel we have lost much of the dedication and caring that once was the hallmark of our profession. We have become so smothered by an overload of information and administration, we deal with behaviors and not human beings. We've lost much of that fine sense of fellowship. Once we had a calling; now we have a job. Nevertheless, I'm very happy that my granddaughter Kelly Krill, like her aunt and grandmother and me, is in speech-language pathology.

first published in ASHA magazine, Jun-July 1989, p. 72-73

reproduced with permission of ASHA

December 28, 2007