A Model for Change From a Consumer's Perspective

About the presenter: Michael Sugarman was co-founder of the National Stuttering Project (NSP) in1977. He became the Executive Director of NSP 1978 -1981 and again in 1995 -1997. Published numerous articles on self help in academic journals and other publications. Recently, named to the Stutterers Hall of Fame. Currently, Chair of International Fluency Association's Suuport Group and Consumer Affairs Committee.

A Model for Change from a Consumer's Perspective

by Michael Sugarman

Los Angeles, California

For 22 of my 44 years I allowed myself to be controlled by a behavior: Stuttering. Stuttering was an obstacle for me to be myself. Specifically, stuttering made it difficult for me to express my wants and feelings. I stuttered; I got anxious; I was afraid and I worried about what the listener would think of me. I struggled to push words out and when I could not, I felt frustrated and became more afraid to speak. The wave of feelings were helplessness, shame, and guilt. When the words finally came, I questioned whether I said what I meant or just chose words for fluency.

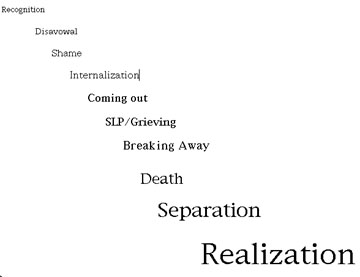

Steps in the Process

The following is a process that I went through to objectify my stuttering behavior. What causes stuttering in one person is not necessarily the same for another person, however, this is how I personally progressed to separate myself from a destructive self concept and assume a liberating self concept. I believe that almost all people who stutter could recall similar episodes that contributed to socializing them into the role of a stutterer. I want to note that the model is cyclical, that one can be in shame and still be in a grieving step.

Recognition

Before attaching sounds to form words and meaning, a child knows, through prior learning, which nonverbal cues and utterances can produce a response. Chomsky (1968) believes that language is not learned; it is recognized by virtue of an innate recognition routine through which children, when exposed to their local language, can abstract and extract its universal grammatical principles. When communicating with words, a child has some end in mind--requesting something, indicating something, or establishing some sort of personal relationship. Bruner (1975) believes that not only does conceptual knowledge precede true language, but so, too, does the child's intention. Children know, albeit in limited form, what they are trying to accomplish by communicating before they begin to use language to implement their efforts. Their initial gestures and vocalizations become increasingly stylized and conventional. Language is not merely encountered--it is encountered in a highly orderly interaction with the parent. What has emerged is a theory of parent-infant interaction. The new picture of language learning recognizes that the process depends on highly constrained and one-sided transactions between child and parent/adult teacher. The child's entry into language is an entry into dialogue and the dialogue is at first necessarily nonverbal and requires both members of the pair to interpret the communication and the intent. This interaction between parent and child is determined by what role each of them performs in communicating their intent. For example, when I entered a situation my parents reacted to me by saying, "Stop. You are talking too fast."

Whenever I engaged in a conversation with my parents the reaction, "Stop," was implanted. Bruner (1975) studied the interactions between six mothers and their 7 month old babies. He found that a large proportion of the interactions involved the mother's efforts to verbally interpret their child's actions. Moreover, each mother sought to standardize certain forms of joint action by the child in such a way as to allow the child to bring his/her attention into line with her own. It seems likely that a child's developing cognitive understanding of the world would be influenced by a barrage of repetitive interactions with caretakers who verbally label and describe his or her own activities and intentions according to their own interpretation.

Bowerman (1976) believes that children may tune out words that correspond to one of their mental constructs, but the recurrence of the same words in contexts toward which they are already cognitively predisposed may well aid their construction of relevant concepts.

Disavowal From A Role

I was unable to discriminate my parent's and other's reactions to me as a stutterer from who I actually am. I wanted to be accepted as a "normal" person. Upon entering a speaking situation, I asserted myself verbally, however, my thoughts of how my parents and other reacted to me were contained in my head: I was different when I spoke; I stuttered. My stuttering behavior and my identity as a stutterer were being intertwined. My identity became tied in with trying to verbalize my thoughts to attain my needs. I became afraid to express my wants and needs. Freud said that the ego was created from how other people saw the child and the way the child viewed how other people viewed him or her. I was unable to disavow my parent's/other's reaction to my speech; that reaction became for me my basic identity. Freud believed that hate arised not from a person's sexual life as is commonly supposed, nor from the frustration of the libido, but as a response to a sense of displeasure by parent or caretaker or friends. I wanted to be listened to. I became frustrated that my needs were not met. As I tried to verbalize my needs, I stuttered. I lapsed into a "whole self" compliance to my parent's reaction to my speech as representing who I was.

Shame

A person learns to play a social role that is organized according to the generalized pattern of norms which define and interpret behavior. In grammar school I was mimicked and laughed at and, in more subtle ways, identified as different. For example, a yellow speech card was placed on the blackboard every Wednesday reminding me to go to speech class. I did not want anyone to know I stuttered, but I knew there was something different about me. I was afraid to talk to anyone about myself. My grades suffered all the way through school.

It is my contention stuttering stigmatizes the person who stutterers by making them feel different from the others in the group. In short, when a person begins to stutter by repeating, prolonging, or blocking, a norm of verbal interaction is left unfulfilled. Verbal interaction operates on fluent speech. When a person begins to stutter, other individuals recognize that this behavior--stuttering--inhibits their understanding of what the speaker is trying to communicate. This is because the listener responds to the words that a person who stutters is trying to say instead of focusing on the ideas. Thus, the listener becomes impatient and, perhaps worse, feels uncomfortable. The normative expectations of verbal interaction are, somehow, not being fulfilled. The norms stutterers have incorporated equip them to be intimately aware of what others see as their failing, engendering the painful knowledge that they cannot live up to the rules of normal verbal communication (Sugarman, 1980).

Internalization

If effective stigmatization imposes penalties and circumscribes access to conventional means of life satisfaction, it may also provide new means to ends sought.

In this author's case, a new phase in the process was developed, which focused on the assumption of the identity of being a "stutterer." I perceived myself as a person who was unable to communicate verbally without stuttering. I was afraid to enter any situation where speech was necessary. The fear of stuttering consumed me. I reduced my expectations and aspirations to conform to the limited opportunities I imagined were available to people who stutter. I was afraid of anything that might involve speaking since talking was something I had avoided for most of my life.

When I entered situations I expected myself to stutter. I created a self-fulfilling prophecy. I needed to stutter in order to know I was a "stutterer." I thus continued to perform in ways that provided an identity for me.

My stuttering permitted me to legitimize my lack of effort to realize my own aspirations. I assumed that, since I could not participate because I stuttered, I told myself, "Why assert myself?" I thus felt cut off from the pursuit of interests and goals, for example, regarding marriage, I thought no one could marry me because I stuttered. In regards to academics, I was afraid to ask a question. As for employment, I could not imagine a profession that would not demand the verbal faculty. And, finally, toward my parents, I was ambivalent (Sugarman, 1980).

Coming Out/Grieving

The person who stutters has been in silent revolt in an attempt to repudiate a self-presumption of inferior status. The stutterer demands to be treated as a person, not as a "stutterer." In other words, the person who stutters wants to be accepted as a contracting individual--as free to contract and take responsibilities as the next person, and not as the occupant of a special inferior status. Therefore, if any change in status does indeed occur, that change must be initiated by that person.

Coming out and "owning" who you are is the essential first step toward change. I hypothesize there are two distinct levels involved in the process of "Coming -Out." One level is the acknowledgement stage where a person begins the process of seeking self- discovery by researching and entering situation wherein something can be learned about the problem that he or she faces. The second level is admission, whereby the person openly confesses to owning the problem; for example, "I stutter."

As I have described earlier, I had to "own" the problem and make a commitment to confront myself before I could realistically think I could "give up" my stutterer identity. I took responsibility that I stuttered. Nobody made me ..... stutter. I stuttered. I learned not to demand from myself what I would not do; that is, I would not conform to what other people considered as verbal fluency.

In speech therapy, I finally confronted my stutter. I talked about how other children mimicked me; how I was afraid to say hamburger and ordered cheeseburgers for 16 years of my life; developed ulcers in the third and seventh grade; was placed in a low reading group. A thought that ran through my mind was, "I once knew a stutterer who died in the gutter because he couldn't utter." I felt sad. I did not like myself.

For one and a half years, I concentrated on dealing with stuttering and myself. I confronted myself as a stutterer; I battled with who I was. I practiced with a tape recorder. I talked about myself. I discovered who I am and what I wanted to do. I was in the University of California at Santa Barbara at that time. In order to actively learn about myself, I participated in classes that involved speaking and counseling. My pastime was to talk about myself as a person who stuttered. I ritualistically took the option to be myself and take control of my script. I lost my fear of interacting with others!

My speech therapist identified my body language for me when I stuttered: eyes blinking, head jerking, muscle tension, neck fastened tightly to my shoulders, repeating words and sounds and mouth held open waiting. This was me. I accept that and realized I wanted to "give up" stuttering. I continued to practice with the tape recorder to learn more about myself. I talked about my thoughts and feelings with and without stuttering, and then listened to me.

With the speech therapist, I became aware of when and how I stuttered. I became conscious of myself. I knew when I was playing a "game" with myself and another person. With my tape recorder I could say, "Oh tape recorder, these words used to make me run away. Today, tell me when I stutter and how. You allow me to hear myself stutter. Yes, good friend, I am happy that we are working together" (Sugarman, 1979).

Breaking Away

I hypothesize that there are five levels to "breaking away" from the "stutterer" identity. First, to recognize when he or she is stuttering, how he or she is stuttering; and with whom he or she is stuttering; second, to admit to anticipating that he or she may stutter on the next sound, word, or sentence; third, to acknowledge that an inner dialogue may exist to inhibit what he or she wants to express verbally; fourth, to become aware of the symbiotic relationship of being a "stutterer" versus a person who may stutter; and fifth, to "let go" of an identity that dictated how he or she will act with the social world.

I saw my social role--"stutterer"--as inhibiting what I wanted to accomplish in my life. At the age of 23 years, an event took place that that provided me the incentive to break away from being a stutter. On the campus of University of California, Santa Barbara, a bulletin read, "Apply to represent the University of California as a student intern in Sacramento. My first reaction was, "Wow! I would like to apply." I wrote down the room number where to apply. I began to walk to the room. I remember my inner dialogue began to talk to me. "Michael, you will have to go through an interview process. How can you expect to do well. You will probably stutter." I stood at the door of the room where I asked for an application. Upon receiving the application, my initial feelings were of being afraid.

My inner dialogue told me, "Michael, you will have to talk to people." I decided to take the risk and to allow my wants to emerge. I applied. I asked for two professors for recommendations. I was interviewed. During the interview, I told myself, "I want to express what I want to say. If I stutter, so what, as long as I am communicating my thoughts and am understood." I went to Sacramento (Sugarman, 1980).

Death

I allowed myself to "give up" my stutter. After becoming clinically fluent, I was told by the speech therapy department that there exists a 90% regression rate to stutter six months following therapy. I felt helpless without my stutter. Twenty-two years have passed and my "stutterer" remains dead. I feared losing a part of me. However, I reaffirmed the contract to be myself. I was no longer shackled to the pattern of my stutter. I look forward to verbal interaction and social occasions and personal disclosures. I talk about who I am. My "inner dialogue" about how I was going to stutter ceased. I grieved my stutter on all levels.

Separation

"If I stutter, it does not matter. I am okay." I allowed myself to separate my symbiotic relationship. I am now a person who may stutter. My new self concept allowed me to take risks. I did not expect myself to stutter. I took a different perspective to interactions. I interpreted an interaction not from how I once behaved, or would behave, and what I wanted to communicate. I was not accustomed to expressing my feelings and desires. However, I placed myself into situations where I wanted to be. I assumed a new perception to myself and others, of events, acts, and transformed my attitude from a new status. I was no longer a "stutterer."

Realization

My stuttering became an almost incidental behavior pattern. I learned to confront my stuttering and use it as a source for informing myself what is doing on for me. I came to realize when and how I stuttered. I developed a relationship with my stuttering. Stuttering helped me to feel in charge of my behavior. It was my ally. It no longer dominated me. I recognized myself as a person with a disability, but I no longer believed I needed to tie my life expectations to that handicap.

Now, I welcome personal interaction. I am no longer afraid to talk on the telephone. I freely order in restaurants. I am able to express my feelings. The stuttering phenomenon now helps me to understand myself. I have come to look upon stuttering as a useful tool, but one that I need less and less.

References

Bowerman, M. (1976). Semantic factors in the acquisition of rules for word use and sentence structure. In Moorhead and Moorhead (Eds.), Normal and Deficient Child Language. State College, PA: University of Park Press.

Brown, R. (1965). Social Psychology. New York: The Free Press.

Bruner, J.S. (1975). The ontogenesis of speech acts. Journal of Child Language (2), 1-9.

Bruner J. (1978). The mother tongue. Human Nature(1), 42-50.

Chomsky, N. (1968). Language and Mind. New York: Harcourt and Brace and World.

Farrel, R. (1976). A causal model of secondary deviance: The case of homosexuality. Sociological Quarterly (17).

Freud, S. (1937). Construction in Analysis, S.E. Vol. xxiii (2nd Ed.), p. 267.

Goffman, E. (1963). Stigma. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Parsons, T. (1970). Social Structure and Personality. New York: The Free Press.

Strauss, A. (1959). Mirror and Masks--The search for identity. Glencoe, IL: The Free Press.

Sugarman, M. (Jan, 1979). From being a stutterer to becoming a person who stutters. Tranbsactional Analysis, 9(1).

Sugarman, M. (1980). A personal account. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 149-157.

submitted August 20, 1998